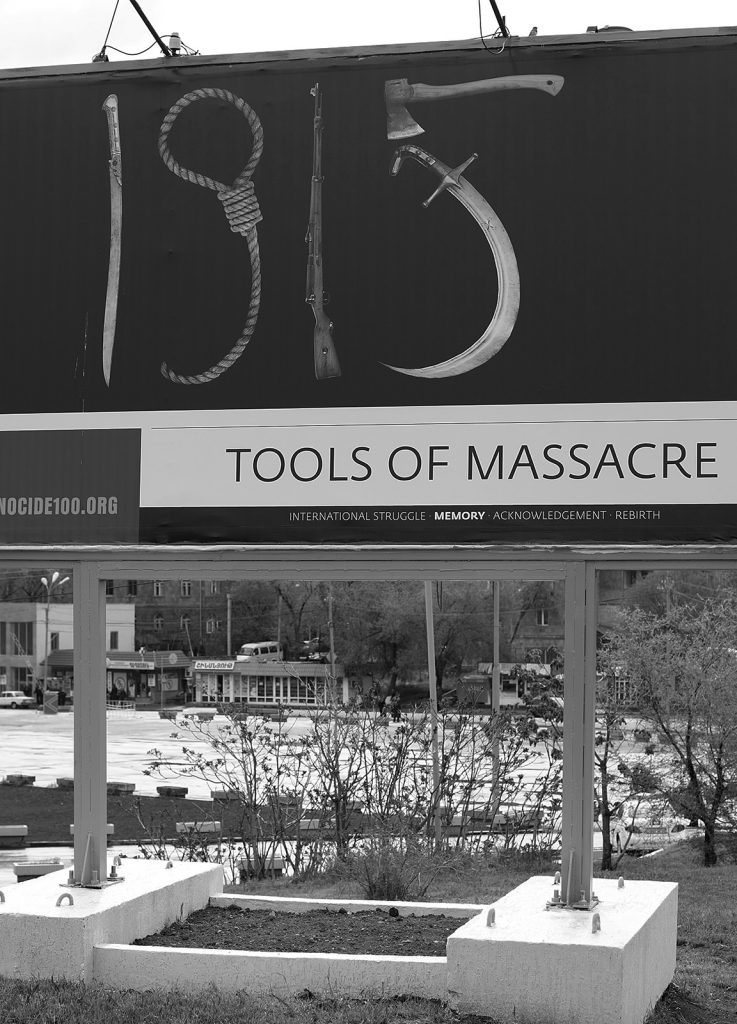

The first 1, a sharp-edged sword; the 9, a rope with a noose; the other 1, a rifle pointing to the sky; the 5, an axe over an Ottoman saber: 1915. It’s April in Yerevan and one expects to find all kinds of posters recalling the massacre, but none this crude. The first entry in my notebook: “What can be built from a pain this great? What insurmountable obstacles does it entail?”

During the weeks prior to the centennial, the media redirected their attention to the forgotten Armenia. Most of them followed the trace of pain printed on the Yerevan poster; others, the international repercussions of Pope Francis’s condemnation or the declarations of countries such as Austria or Germany, which, at the last minute, joined the short list of 26 states that recognize the first genocide of the 20th century. Like many other colleagues, a team of journalists from Contrast traveled to the country drawn by the persistent memory of its people, but also determined to go a bit further. We asked ourselves, and continue to ask ourselves, how this memory interacts with the identity and the future of a country permanently located at a multitude of crossroads. The final objective: to generate a debate which, while essential for Armenia, can inspire other realities.

It seems as though there are two Armenias: the one that bears and struggles with the heavy burden of a gloomy and maladroit present, and the one that gains momentum in order to turn memory into a demand for justice.

Geostrategy and peace

The first crossroads the country encounters is historical and can be measured in square kilometers. Armenia is a small state of three million people which, while retaining only a fraction of its original territory, still maintains the same geostrategical importance that has led it to be continuously invaded by neighboring empires (Ottoman, Persian, Russian, etc.) throughout its history. To the west, the border is closed. The Turkish state is still the great ally of Western powers in the region, which explains the lack of support for the cause to gain recognition of the genocide perpetrated by the government of the Young Turks between 1915 and 1923. Every year, President Erdogan expresses “sorrow” for the death of thousands of Armenians “in the context” of the First World War but, along the lines of his predecessors – and shared by countries like the US, Spain or Israel – does not recognize the existence of a planned massacre as such. Meanwhile, to the east and southeast of Armenia, Azerbaijan has been on the warpath since 1991, when the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which has cultural and historical Armenian roots, proclaimed its independence in the midst of an escalating war between the two countries. Despite the ceasefire signed in 1994, the trickle of soldiers killed at the border of this de facto state, unrecognized by any other state in the international community, is continuous and nothing suggests that it will end anytime soon – quite the opposite. The death toll has increased considerably over the past few years (34 in 2012, 72 in 2014) and the situation is still at a stalemate. Perhaps it is time to listen to local organizations like Peace Dialogue that have been working for years to disseminate peace culture in the region.

The landless flower

The second crossroads is temporary and has to do with the geostrategic crossroads and the direction the country wants to follow in the short term. During the fifteen days we were there, we were able to understand how the economic crisis Armenia is in does not only call into question its alliances in the region, but also the foundations of its identity. First of all, it calls into question its alliance with Russia. The government of Serzh Sargsyan has strengthened economic and military ties in search of a strong ally, but the move hasn’t paid off: the crisis that is already shaking Moscow has hit the weakened Armenia full on. In the last few months, remittances from 200,000 migrant compatriots who work in Russia have decreased (21% of the Armenian economy depends on remittances, 80% of which come from Russia) while the prices of basic services supplied by Russian companies have gone up. Last June, the protests of thousands of people in the streets of Yerevan forced the government to call off a planned 17% electricity rate hike.

International recognition of the Armenian genocide is conceived not only as an ethical demand, but also as an opportunity for progress

Apart from the passions and phobias aroused by the alliance with the Putin government, the massive emigration triggered by the crisis has spurred, in front of our cameras, another debate: What does Armenia need to recover? Endemic corruption and repatriation policies aimed at the eight million Armenians living outside the country came into play in the debate, but so did the fear of a progressive loss of identity. “It’s like pulling a flower from its habitat and taking it somewhere else: it will be subjected to a short life,” historian Gevorg Yazedjian told us at his home. Like him, many members of the diaspora that we interviewed fear that the two-pronged effect of migratory processes and globalized life will cut the roots of a millenary culture that has always been a beacon and a shield in the face of all kinds of danger. Including genocide.

It is difficult to speak with a minimum of authority, and even more so from this simplifying distance, but it would seem that two Armenias soar over the country. One that bears and struggles with the heavy burden of a gloomy and maladroit present, and another one that gains momentum from the past in order to turn memory, not only into an imperative of identity, but also into a demand for justice. In the eyes of this Armenia, sustained mostly by the families of the survivors who were expelled from the country one hundred years ago, international recognition of the genocide is conceived not only as an ethical demand, but also as an opportunity for progress, since admitting its existence would open the way to a legal return of properties seized by the killers in the massacre of 1915. With this in mind, dozens of Armenian lawyers around the world have for years been collecting the documentation needed for justice to be revived. Only then, they say, will it be possible to make the country a more prosperous and democratic land. The land where the flower must survive.

Photography : Jordi de Miguel Capell – Poster recalling the massacre in Armenia –

© Generalitat de Catalunya