When reading about United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325, it is very common to see the word ‘landmark’ appearing in front of it. This is because the passage of the resolution in 2000 was seen as a watershed moment for women’s rights activists, many of whom had been arguing for years that gender issues must be taken seriously in all efforts to promote peace. UNSCR 1325 – the first of seven resolutions on women, peace and security1 – was among the first to be conceived and lobbied for by civil society. And while gender and women’s rights had long been topics of discussion at the UN, before 2000 they had never been deemed relevant for debate at the Security Council. I still remember hearing about 1325 for the first time, and thinking it miraculous that these brilliant feminists had convinced the UN’s highest authority on international security that women’s rights matter for peace and security.

But even among those of us who champion 1325 (and its sister resolutions) and continue to call for faster implementation, there are also reservations. Preparations for this month’s UN High Level Review on women, peace and security have prompted a great deal of introspection over the past year among what might be called the ‘women, peace and security community’. For some, the concern is simply that governments haven’t moved quickly enough to fulfil their commitments, or haven’t taken the resolutions seriously enough. For others, the problems run deeper: the language of the resolutions isn’t quite right, or simply isn’t radical enough to reflect feminist critiques of the international community’s current approaches to maintaining peace and security.

In my work as a gender adviser for an international peacebuilding organisation, I work with many women activists both in countries affected by violent conflict and in peaceful contexts. Most agree that 1325 has been an important counterpoint to conventional understandings of what matters in resolving conflict and building peace. As Carron Mann, Policy Manager at Women for Women International UK put it, “The women, peace and security framework challenges ‘traditional’ concepts of conflict, which are heavily masculinised and focused on weaponry and resources. In these concepts, women are civilians caught in the crossfire, who should ideally be protected, but casualties will inevitably happen. This ‘traditional’ concept reflects wider systems of patriarchy which similarly objectify, subjugate and abuse women both in and out of conflict.”

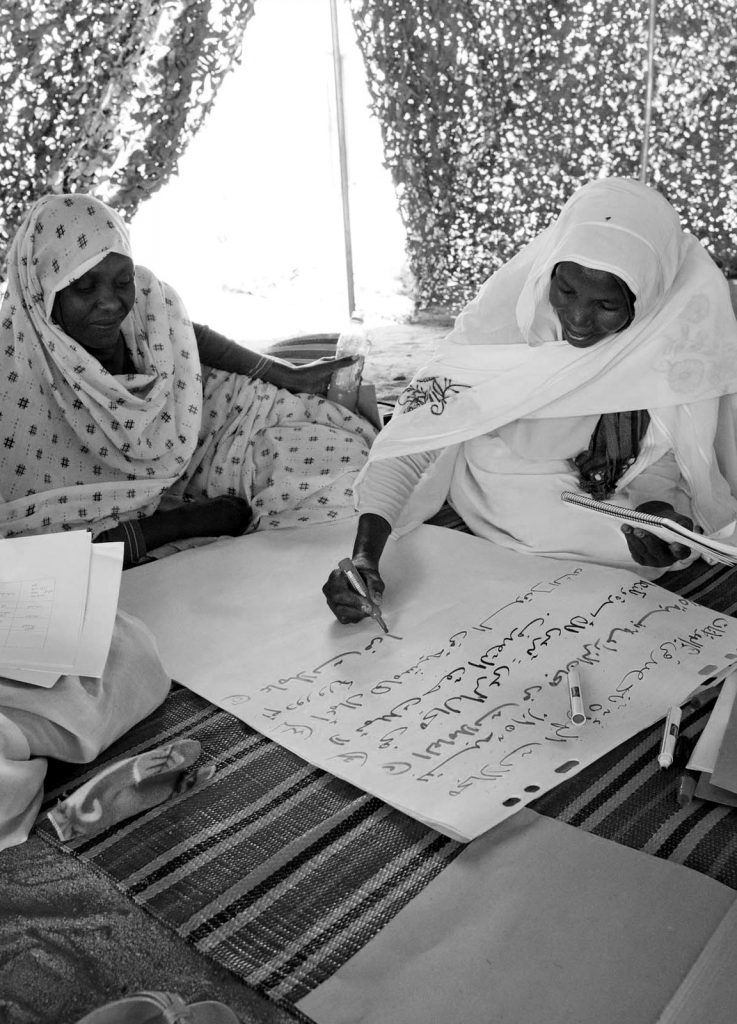

For women experiencing violence and oppression in their everyday lives, UN resolutions can seem like a remote concept

Yet despite the celebration of 1325 and the huge amount of advocacy happening around it, there are limits to how it has been integrated into the work of women’s organisations working for peace. For example, while there has been much lobbying of the UN and national governments, the resolutions often have less traction at the local level. “Grassroots advocacy is yet to find 1325 a useful tool,” says Mann, “We work with marginalised women in countries affected by conflict, many of whom are essentially confined to their households and not connected to networks or women’s groups. There is little ‘grassroots’ advocacy around 1325 in communities.” Isabelle Geuskens, Executive Director of the Dutch organisation Women Peacemakers Program, agrees: “Usually experts on women, peace and security are very knowledgeable but they’re not always well-connected to the grassroots women. They regularly struggle to reach and mobilise people at community level, which is important to create a constituency that can push for change from the bottom up. For me the future of 1325 will lie in investing in social mobilising space and skills.”

Indeed, for women experiencing violence and oppression in their everyday lives, UN resolutions can seem like a remote concept. While working in the Occupied Palestinian Territories in 2008 I interviewed a number of women from different organisations and political affiliations about their activism. When asked about the impact of 1325 on her work, one woman told me: “I know Resolution 1325, about women in conflict and wars. It hasn’t really helped us. It’s just a resolution.” For Palestinians, like many other populations who feel left behind by the international community, innumerable laws and policies have been adopted which purport to guarantee their rights but amount to little in practice. It is therefore no surprise that 1325 appears to them as a cruel fiction.

Some countries, despite experiencing serious instability and violence, are not described as conflict zones and therefore 1325 is often not thought of as applicable to their contexts

In some contexts, the barriers to using 1325 as an advocacy tool spring from questions over how the resolution is interpreted. For example, despite the fact that 1325 calls on all UN Member States to increase women’s participation in decision-making on the prevention, management and resolution of conflict, this provision is often implicitly interpreted as referring only to countries currently experiencing or emerging from armed conflict. The nature of today’s conflicts is truly transnational: civil wars such as those in Syria, Libya and South Sudan involve not only their national governments and rebel groups, but global and regional powers such as the USA, EU, China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Yet these countries – even those which have National Action Plans on Women, Peace and Security – rarely see the increased participation of women in their own foreign and defence policy-making as a priority under 1325.

Some countries, despite experiencing serious instability and violence, are not described as conflict zones and therefore 1325 is often not thought of as applicable to their contexts. In Egypt, for example, women activists have largely chosen not to use 1325 as an advocacy tool. Dalia Abdel Hameed, Gender and Women’s Rights Officer at the Egyptian Institute for Personal Rights, posed the question, “If you look at the current situation in Egypt, is it post-conflict? Post-revolution? Post-uprising? It’s a very difficult task to describe it. During 2011-13 we witnessed violent clashes, and huge protests and demonstrations. While we are not experiencing this now, it is still hard to say that we are over the violence. The oppression is omnipresent but the forms are different – most of the revolutionary groups are now under a crackdown, and there is a wider climate of oppression. People are trying to convince us to use 1325 in Egypt, but using the resolution first needs civilian rule, rather than military rule, which is not the case in Egypt.”

For some women activists, the stumbling block in using 1325 in their advocacy lies not in its interpretation, but in the content of the resolution itself. While the provisions of the women, peace and security resolutions are an important step forward, and in some contexts have brought real changes to women’s lives, they fall short of the radical re-envisioning of international security which many feminists seek. On this view, the goal is not only to increase women’s participation in existing systems for resolving conflict, but to promote less militarised, less masculinised approaches to security which can help prevent conflicts from breaking out in the first place.

Although women, peace and security advocates have tried to use 1325 to promote demilitarisation, the text of the resolution itself is less ambitious. As Isabelle Geuskens puts it, “As women activists we had this vision of how we saw peace, and in 2000 we got this resolution and perhaps we just projected all of our wishes on to it. Good advocacy sometimes means you take a tool and you use it creatively. But there seem to be many limits in terms of how much of what we really want can be achieved via this resolution, and therefore we need to rethink how we are going to reclaim the more radical parts of our vision.”

The goal is not only to increase women’s participation in existing systems for resolving conflict, but to promote less militarised and masculinised approaches to security

The worry, then, is that by calling on world leaders to incorporate women and their concerns into the current, militarised international system, we allow ourselves to be co-opted by it. According to Geuskens, “In the past, we have seen strong voices from women’s movements that were redefining what security means, questioning militarisation, the arms race. But so much of the energy around 1325 has been focused on working within the systems of power, to the extent that some people within the women, peace and security community would get very uncomfortable when you would bring up issues of militarism and the need for disarmament.”

But despite these misgivings, most women peace activists still agree on the importance of using 1325 as a point of leverage for bringing women and their concerns to the table. “I definitively don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater,” says Geuskens, “I remember what it was like to not have 1325. It has helped women to get a voice. Although women are often still ignored, the arguments to justify their exclusion are becoming more and more thin.” This month’s review provides a crucial opportunity both to ask critical questions about the shortcomings of the women, peace and security framework and how we have used it, and to call on world leaders to make good on their commitments and implement the resolutions in full.

1. This article was written before the approval of UN Resolution 2242. So, now, there are actually eight thematic resolutions on Women, Peace and Security.

Fotografia : The Institute for Inclusive Security

© Generalitat de Catalunya