The first tweet about Mara Salvatrucha in Donald Trump’s official account was written on 20 April 2017, exactly three months after his swearing in as president of the most powerful country in the world. “The weak illegal immigration policies of the Obama Administration allowed bad MS 13 gangs to form in cities across US. We are removing them fast!” With these words, Trump began something that later became constant: the use of the mara phenomenon (and one in particular, Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13) to justify his discourse and his anti-immigrant policies.

But what are the maras? Trying to summarize such a complex phenomenon in one paragraph is audacious, and perhaps even ill-advised, but here goes: The maras are very violent youth groups that originated in Los Angeles area, California. Beginning in the early nineties, they began to gain adherents in the Central American region through the mass deportation of active members of the two Latino gangs most inclined to accepting Central American migrants in their ranks: MS-13 and Barrio 18. The first deported members of these gangs did not take long to make their respective gangs grow in a social environment characterized by poverty, inequality and violence, coupled with extreme institutional weakness and a state presence that is either non-existent or insignificant. In less than a quarter of a century, these groups made up of youngsters and adolescents went from being a problem of public safety to a problem of national security, especially in El Salvador, where they developed the most. These gangs are fragmented, very territorial and ultraviolent, and they have demonstrated a great capacity for adapting to the public policies with which different governments have tried to combat them, almost all of which are strictly repressive. Today, after thirty years of evolution based on the conditions in Central American societies, the MS-13 operating in San Salvador or in Tegucigalpa has little to do with its homonym in Los Angeles. Referring to Mara Salvatrucha or the Barrio 18 gang as a whole, as a kind of multinational crime syndicate, is one of the most recurring errors among academics, journalists and even authorities in charge of neutralizing the threat they pose.

Referring to Mara Salvatrucha or the Barrio 18 gang as a whole, as a kind of multinational crime syndicate, is one of the most recurring errors

From the outset, I have been a member of “Sala Negra,” an investigative team set up in 2010 by the Salvadoran digital newspaper El Faro to try to dissect and understand the various expressions of violence in the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras), the region the United Nations considers to be the most violent on the planet. Because of their aggressive presence in the daily lives of millions of Central Americans, the maras have been the habitual target of our investigations, which have been characterized by very intense reporting in the communities most affected by this phenomenon, and a direct and sustained dialogue with victims and victimizers.

The central theme of this issue of the Peace in Progress e-magazine came up from our first approaches: violence related to drug trafficking. Were – or are – maras key actors in the transportation of cocaine between the Andean region and the nostrils of gringos? Are they a real threat to the world’s most powerful country, as inferred from the increased importance attached to MS-13 in Donald Trump’s speeches?

Since the beginning of the century, apparently serious reports and investigations – funded mostly by US institutions, or directly with federal funds – link Barrio 18 and especially Mara Salvatrucha with international drug trafficking, but these assertions do not fit with our inquiries on the ground. Our investigations find that most gang members and their families have much more mundane concerns, such as ensuring they get three meals a day. Washington wound up stirring up a hornet’s nest when, at the end of 2012, the Treasury Department included MS-13 on its blacklist of transnational criminal groups, along with organizations such as the Zetas, the Yakuza or the Camorra. The Mara Salvatrucha of Guatemala, of Honduras, of El Salvador and the one that operates in Mexican territory – mostly in the south – are not all the same after these three decades of parallel evolution. Even in El Salvador, the case that we know the best, assigning the same role to all of MS-13’s “cliques” (the gang’s basic unit of operation) and “programs” (chapters: groups of cliques that operate under the same command) is absurd. Not even in such a small country, of little more than 20,000 square kilometers, is such an unreserved generalization wise.

Maras traffic in and consume drugs, that is an irrefutable fact. But their main role in the distribution chain is small-time drug dealing: in kilograms, not in tons.

In “Sala Negra” we set out to answer once and for all the question of how important MS-13’s role was in international drug trafficking. An investigation conducted in collaboration with The New York Times, lasting over six months, gave rise to a report published simultaneously by both publications in November 2016, the English version of which was entitled Killers on a Shoestring: Inside the Gangs of El Salvador. The article is extensive, solid, accurate, and of course you are welcome to read it in its entirety, but I have extracted a paragraph that fully illustrates the theme of this column: “Although Salvadoran gangs sell drugs, they do it like street-corner dealers, not international operatives. From 2011 to 2015, the National Police seized 13.9 kilograms of cocaine from gangs; that was less than 1 percent of the total seized. Three-quarters of the gang members prosecuted on drug charges over the last few years were charged with possessing less than an ounce.”

Two years have gone by since the publication of that report, but we have no evidence that there have been any substantial changes, and much less certainty that MS-13 or the Barrio 18 gang have become major international drug trafficking operators, or that as gangs they even maintain a relationship of equals or of dependence with any of the Mexican cartels that supply the US market.

Maras traffic in and consume drugs; that is an irrefutable fact. But their main role in the distribution chain is small-time drug dealing, protected by the aggressive territorial control they maintain in the neighborhoods and communities they dominate. It is likely that some clique or “program” in particular has made the leap and is dealing in more significant quantities, but always measured in kilograms, not in tons.

Regarding reports and investigations that affirm that Central American gangs play a decisive role in global drug trafficking, I cannot but question the researchers’ methods of investigation, which must be superficial, biased or hasty, or even their interests or those of their financial backers.

The relationship between maras and international drug trafficking is embryonic

That in the medium or long term maras may become more involved should not be ruled out; on the contrary, it is likely and even logical. Therefore it is advisable to keep in mind that, especially Mara Salvatrucha (the most organized and hierarchical, within the atomization and operational autonomy of the cliques typical of this phenomenon), or a select group of its members, could end up becoming a much more articulate actor capable of moving tons across the many borders of the Central American region. It may even have already begun to move in that direction in Honduras or Guatemala, where the maras have a tougher competition with narco-traffickers in terms of territorial presence.

On this side of the Atlantic, the expression Asustar con el petate del muerto (Scare with the dead man’s shroud) is often heard. We use it when someone or something wants to provoke anxiety without there being a cause that justifies it. I am not able to say by whom or why we have been scared by the dead man’s shroud for years regarding the issue of the relationship between maras and international drug trafficking, but I can say that this relationship is, in any case, embryonic. Maras constitute a problem that brutally affects the daily lives of millions of Central Americans, and their members generate death, forced displacement and ruin every day. The diagnosis needs to be as accurate as possible if we really want to solve this problem.

Roberto Valencia has published Carta desde Zacatraz (Libros del KO, Madrid, 2018) on the maras phenomenon

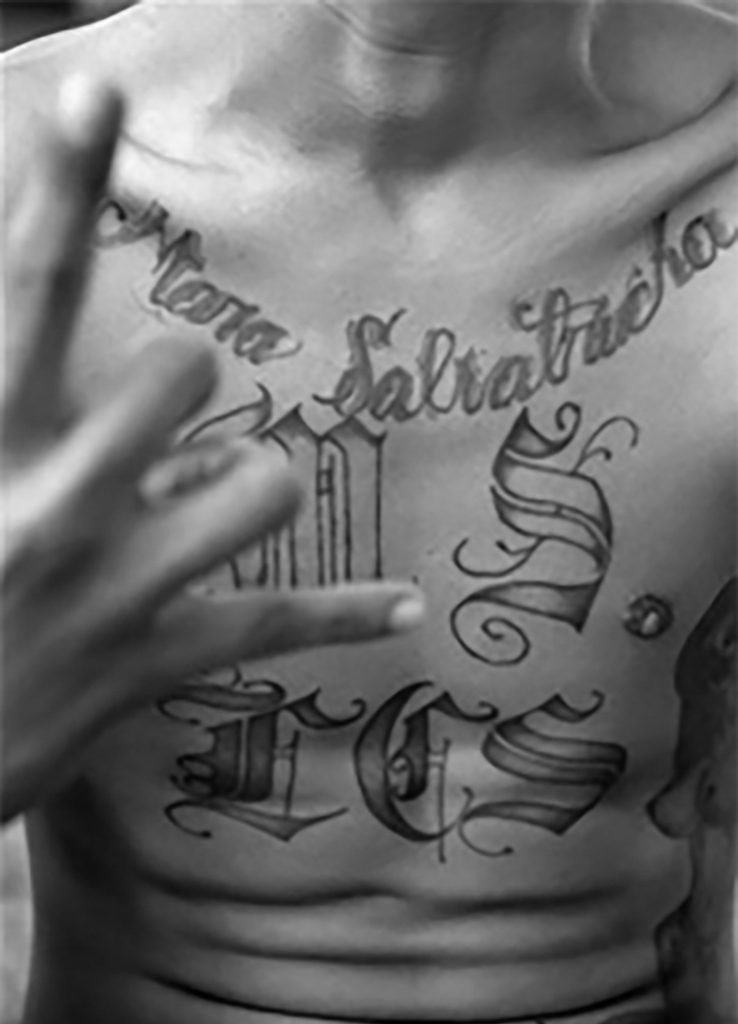

Fotografia : Tattoo member of the “Maras”

© Generalitat de Catalunya