As a peacebuilding institution, ICIP has repeatedly dealt with realities associated with the phenomenon of enforced and involuntary disappearances, particularly in countries such as Mexico or Colombia. Considered one of the most serious human rights violations, enforced disappearance poses a huge challenge to peacebuilding processes, both in contexts of post-conflict transitions and in areas with high levels of state and criminal violence. In these contexts the need for truth, justice and reparation are essential conditions for coexistence and reconciliation. This process also provides guarantees that the population can live with the certainty that such events will not take place again in the future.

The number of enforced disappearances around the world is appalling. It is estimated that more than 60,000 people have disappeared in Mexico between 2006 and 20191; over 80,000 in Syria since 2011; between 60,000 and 100,000 in Sri Lanka from the late 1980s to 2009; about 30,000 during the Videla dictatorship in Argentina2; and, in Spain, it is estimated that about 114,000 people disappeared during the Civil War and the Franco regime3.

Behind all these figures and other realities beyond this dismal tally, there are people with a name and a story, families with the painful anguish of not knowing if their loved ones are dead or alive, if they are cold or hungry, if some day they will return, or where they have been buried. Beyond individual suffering, the practice of enforced disappearance imposes fear and mistrust among communities and, in many cases, it even distorts or erodes the social fabric. It goes without saying that a social pact based on states as guarantors and promoters of human rights is drastically altered when a government resorts to enforced disappearance or fails to take appropriate measures to search for the missing.

Considered one of the most serious human rights violations, enforced disappearance poses a huge challenge to peacebuilding processes

There are, nonetheless, numerous cases of resistance to this practice; initiatives by families and groups calling for truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence. This often involves starting off on a path with little or no state support; a path where one encounters silence, pain and loneliness, but also the company of other family members in the same situation.

Families, and women in particular, who, faced with the psychosocial impact and breakdown of the social fabric resulting from disappearances, decide to join forces to find their relatives and also to discover the truth about what happened and to prevent any repetition in the future. By so doing they become fundamental agents for coexistence, memory and reconciliation. In many occasions, such processes result in personal and collective empowerment.

ICIP wanted to acknowledge the relevance of one of these experiences by granting the Peace in Progress Award 2019 to the Coalition of Families of the Disappeared in Algeria (Collectif des Familles de Disparu(e)s en Algérie, CFDA). This award aims at recognizing their work to clarify the enforced disappearances committed during the 1990s Civil War in this North African country, as well as their struggle to achieve a peaceful and democratic transition with the establishment of a process for truth, justice and reparation and the full observance of fundamental human rights and freedoms.

ICIP has published this monograph with the purpose of offering elements of reflection and awareness about enforced and involuntary disappearances in different contexts, as well as giving visibility to the struggle for truth, justice and reparation of many groups of relatives of the disappeared. An effort has been made to understand enforced disappearances from a people-centered perspective aimed at contributing to the building of peaceful societies. The intention is to look beyond mere legal aspects of disappearances and instead emphasize the impact on people’s lives and subsequent accountability.

The number of enforced disappearances around the world is appalling. More than 60,000 people have disappeared in Mexico between 2006 and 2019, and over 80,000 in Syria since 2011

Historically, the profile of a forcefully disappeared person has been closely linked to that of a political dissident kidnapped and killed by an oppressive regime. However, reality shows that people also disappear in much more diverse circumstances: from the false positives in Colombia to the women and children who disappear in sexual exploitation networks; or from the disappearances associated with the war on drugs and the violence of organized crime, to the disappearance of people on migratory routes. In consonance with a recent report by the United Nations Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances4, ICIP has considered it appropriate to focus on the latter. It is indeed a reality that is occurring just a few kilometers away from our country and is not unrelated to European immigration policies; policies that undermine the very values on which liberal democracies were built and the European Union itself.

There are bodies at the bottom of the Mediterranean or in graves along desert routes. The changes of finding them, or of migrants regaining their freedom after they have been abducted or deprived of liberty for political or human-trafficking reasons, fade away due to a lack of cooperation and action by the authorities in establishing judicial and forensic mechanisms for the investigation, support and reparation of the victims.

In this monograph, the ICIP has made an effort to understand enforced disappearances from a people-centered perspective aimed at contributing to the building of peaceful societies

In the meantime, families keep waiting in their countries of origin without any news, trying to shed light on the facts from afar and demanding truth and justice.

In light of this broad scope, the monograph begins with an article by researcher Elisenda Calvet. Calvet offers a general outlook on enforced disappearances and how they are connected to processes of transition to peace and transitional justice. The way cases of enforced disappearances are managed is crucial for the success of such contexts.

In the next article, the renowned human rights advocate Theo van Boven highlights the importance of breaking with states’ denial of enforced disappearance, as was the case during the Argentine dictatorship. Van Boven argues that countering states’ denial is key to the trilogy of justice, where victims are at the center: the right to know, to redress and to reparation.

In the third article, Marije Hristova deals with the particular case of Spain, as an example where the struggle for historical memory has resurfaced among the generations that came of age after the violence. Relatives of the disappeared have played, and continue to play, a crucial role in the search for mass graves and the identification of bodies decades after their enforced disappearances were committed.

Beyond individual suffering, the enforced disappearance imposes fear and mistrust among communities and it distorts or erodes the social fabric

In her article, Karla Salazar elaborates on the concept of human resilience. She insists that accompanying relatives of the missing is extremely important to strengthen their capacity of resilience in the face of a loss that is as ambiguous as distressing.

These impacts also need to be analyzed from a gender perspective. In the case of Syria, where most of the disappeared are men, Anna Fleischer tells us about experiences where women carry out tireless research, often joining forces with families of other victims of disappearance, which at the same time contributes to the strengthening of the social fabric and their own empowerment.

In light of these processes of healing and rebuilding the social fabric, Alejandro Valderrama recounts in his article experiences from Colombia in which art and culture have played a facilitating role. These events have also built collective memory through life experiences and individual pains, and brought personal ordeals to the public arena.

This monograph was inspired by all the people who have come together, despite the dangers they face, to look for those that others have wanted to cast into oblivion

Finally, the last two articles exemplify causes and impacts of enforced disappearances within the framework of migratory processes. Corina Turlbure and Wael Garnaoui highlights the relationship between European migration policies and cases of enforced disappearance in the Mediterranean. Karlos Zurutuza illustrates the case of Libya, where the combination of a migratory route, the lack of a state structure and the presence of hundreds of armed groups is fertile ground for a great number of human rights violations, including enforce disappearance. Under these circumstances, investigating cases of disappearance, providing reparation to victims and guaranteeing non-recurrence of the crimes presents extraordinary challenges.

Complementing these articles, this issue includes an interview with four women who are relatives of missing persons. These women, from different backgrounds and life experiences, promote the search for their loved ones and the truth about what happened through social and political action. They are Nassera Dutour, from Algeria; Gladys Ávila, a Colombian residing in Sweden; Yolanda Morán, from Mexico, and Edita Maldonado, from Honduras.

Lastly, this issue includes a series of recommendations of books, articles and videos for those interested in enhancing their knowledge about enforced and involuntary disappearance.

1. According to a report by the Mexican government, as of 31 December 2019, there were 61,637 people “disappeared or not found” in the country.

2. Amnesty International: “Enforced Disappearances” (last visit 21/04/2020).

3. Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances of the United Nations: Report of visit to Spain in 2013.

4. Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances of the United Nations: Report 2017.

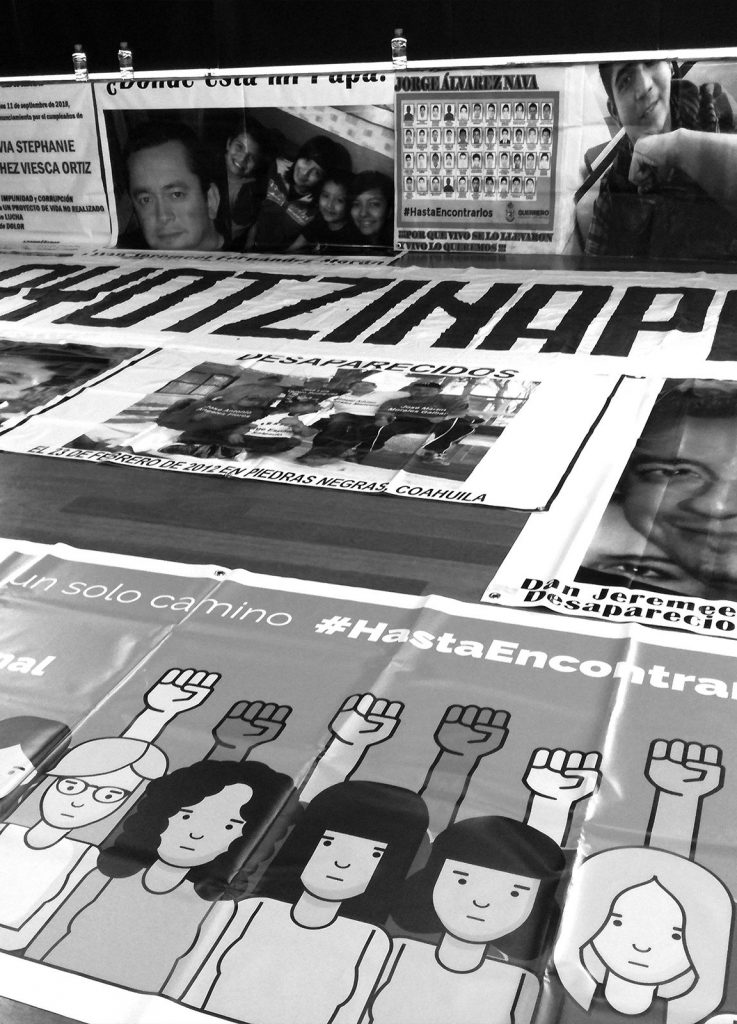

Photography Memorial ceremony of the fifth anniversary of the forced disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, in Mexico, during the I International Forum on Peacebuilding in Mexico, organized by the ICIP, Serapaz and Taula per Mèxic in September 2019, Barcelona.

© Generalitat de Catalunya