Item 5 of the final agreement to end the armed conflict and build a stable and lasting peace, signed by the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army (FARC-EP) on 24 November 2016, concerns the victims of the armed conflict. This point establishes a comprehensive system of truth, justice, reparation and non-repetition, including a special jurisdiction for peace and a commitment to human rights. The objectives of this system are to achieve the realization of victims’ rights, to ensure accountability, non-repetition, a territorial-based approach, legal security, coexistence and reconciliation, and legitimacy. Its components are the Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition Commission (hereafter the Truth Commission or the Commission); the special unit for the search for persons deemed as missing in the context of and due to the armed conflict; the Special Jurisdiction for Peace; the comprehensive reparation measures for peacebuilding purposes; and the non-repetition guarantees.

The Truth Commission provided for in the agreement will have a duration of three years and a preliminary phase of six months to prepare everything necessary for its operation. A precise investigation period has not been established; the Commission itself will establish it, possibly determining a longer contextual period and a shorter clarification period. Its main objectives are to contribute toward the historical clarification of what happened, promote and contribute to the recognition of the victims, and to promote coexistence across the country. It will consist of eleven commissioners, no more than three of whom can be foreigners. The efforts of the Commission will focus on guaranteeing the participation of the victims and it will be able to hold public hearings; it will clarify the practices and actions that constitute serious human rights violations and serious breaches of international humanitarian law; it will include territorial, differential (a reference to indigenous peoples) and gender perspectives, as well as the impact of sexual violence; it will establish voluntary recognition of individual and collective responsibilities; it will be an extrajudicial mechanism but it will ensure due process and non-discriminatory treatment; it must implement a strategy of dissemination, education and relations with the media; it will prepare a final report and take measures to preserve the archives once its work is done; and it will create a committee to follow up and monitor the implementation of the recommendations.

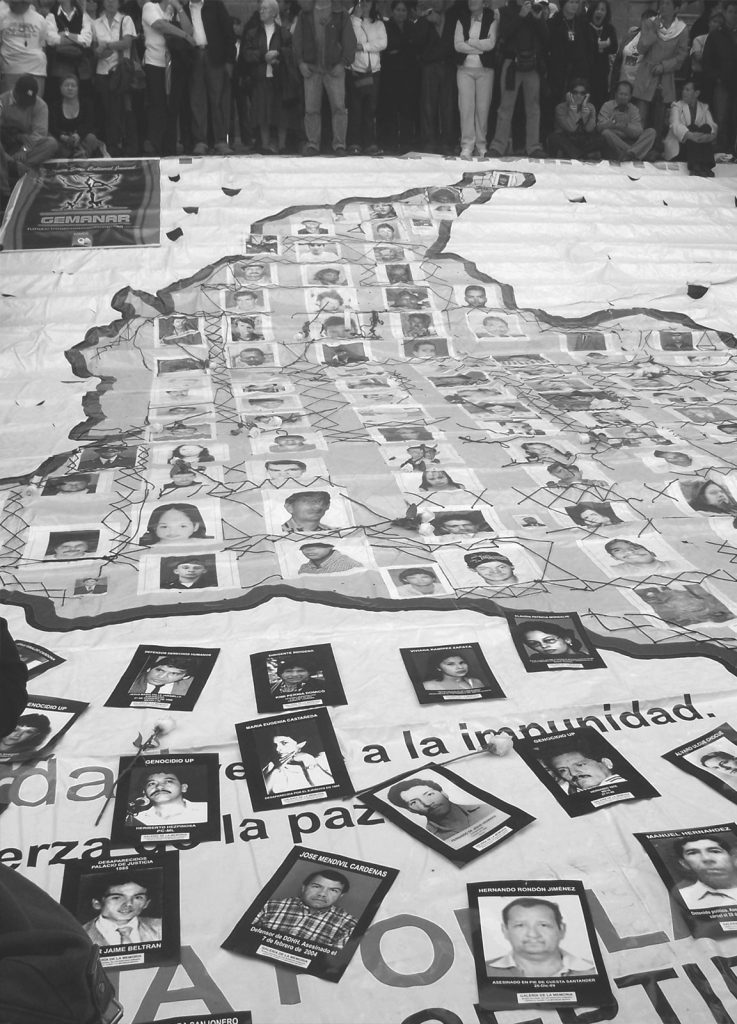

The victims must be the protagonists of the Commission; no one can speak on their behalf and no one can keep them from speaking

The presidential decree creating the Truth Commission was issued on 5 April, transcribing the objectives, guiding principles, mandate and functions outlined in the peace agreement. The most novel aspect of the decree is related to access to information, particularly with regard to classified information, and the functions to be fulfilled by the president, the secretary-general and the plenary of the commissioners.

Several challenges are emerging in the short term for the formation, structuring and operation of the Truth Commission. The first one is the designation of the eleven commissioners, who must guarantee not only their independence, autonomy and impartiality, but also demonstrate great sensitivity to prioritize the demands of the victims and a commitment to the respect for and guarantee of human rights. And the personnel working on the Commission must also have these same profiles. The process of nominations, selection and appointment of the commissioners is expected to be carried out during the second and third quarter of 2017 in order for the Commission to begin its work as soon as possible. Hopefully, in early 2018, the Commission will open its doors, which would mean that it had previously completed its preliminary stage in which it will have to define its methodology, its territorial deployment in the various regions of the country, and initiate an extensive educational campaign to summon the many victims of the Colombian armed conflict to come and testify.

The centrality of the victims is a priority for the work of the future Commission. They must be the protagonists. Above all, it is they who must be listened to because those who speak are the ones who end up making history; that is why the victims must be the ones who tell their story. The taking of testimonies, both individual and collective, and public hearings, are key methodological tools for this process. No one can speak on behalf of the victims and no one can keep them from speaking.

It is to be expected that those who committed acts of violence contribute effectively by telling the truth and asking for forgiveness

The period of years under investigation should be long enough to be in accordance with the seriousness of the political violence. Although the period framing human rights violations and breaches of international humanitarian law for the taking of testimonies may be less than that of a more general context, such a period should be extensive enough to include as many victims as possible. A period of time that does not meet the expectations of clarifying as many acts of violence as possible would not be in accordance with the country’s violent past. Furthermore, the most serious crimes committed during the armed conflict that violated the rights to life, personal and sexual integrity, personal dignity and personal freedom should be investigated. And the most paradigmatic cases which, due to their large-scale nature and impact, have become part of the recent history of Colombia, should also be analyzed.

Guaranteeing the various approaches that the Commission must have is not an easy task in a country that for decades has seen thousands of victims throughout the land, where gender, age, race, ethnicities and political opinions, among other things, have not been respected. These approaches must not only be circumscribed to the facts, but also to the impacts and to the different forms of coping with them, as well as to the inclusion of a differential methodology.

Although the Commission is an extrajudicial mechanism, this should not be an obstacle to establishing the accountability of perpetrators. Hopefully, the Commission will make more progress in unraveling the truth of the perpetrators than other official commissions that Latin America has had. Institutional, individual, collective, national and international responsibilities are part of this clarification function. It is to be hoped that those who committed acts of violence will contribute effectively by telling the truth, assuming their responsibility and asking for forgiveness if they think that they will be favored by the justice measures brought about by the peace agreement.

The Truth Commission reduces at least a significant number of lies that exist in contexts of gross violations of human rights

The final report must be sufficiently comprehensive so that it can provide an official truth of what happened in Colombia during the armed conflict. Its content cannot be reduced simply to the armed confrontation between the national government and the FARC-EP, but must include the clarification of crimes committed by other actors such as paramilitary groups and other guerrilla organizations. Furthermore, the Commission’s work does not end with the final report; it should also offer an accompaniment process to the victims in order to promote coexistence across the country, which is precisely the third objective stated in the agreement. The follow-up to its recommendations will be key to helping rebuild the social fabric of the affected communities. Moreover, the different components of the integral system of truth, justice, reparation and non-repetition must be sufficiently balanced and coordinated, and implemented in a coherent way so that they all fulfill their purposes and do not generate imbalances in each of its components.

It is to be hoped that this mechanism will contribute significantly to the building of a public framework of a memory discourse that establishes a new official paradigm of truth, since the current standards of transitional justice point out that it is one of the mechanisms that more effectively satisfies the right to the truth. If justice is to be administered through a system of penalties where penalties of imprisonment will not be so crucial, high doses of truth are required for transitional justice to be more in line with international standards. As Michael Ignatieff has written, a truth commission at least reduces a significant number of lies that exist in contexts in which serious human rights violations or serious breaches of international humanitarian law have occurred. It would be advisable for the Commission that will soon start to work in Colombia to eradicate some of these lies and establish a truth that contributed more decisively to peace among Colombians.

Photography : Lowfill Tarmak

© Generalitat de Catalunya