The end of violence does not mean the achievement of peace. After armed conflicts, societies enter into periods during which the reconstruction of social relations is key to establishing a harmonious coexistence and overcoming past divisions. The warring parties are faced with the challenge of reconciling themselves and relearning to live together with respect and tolerance. Thus, long and comprehensive processes are initiated, in the sense that they imply a multiplicity of factors: reconciliation requires looking at the past, confronting it and trying to rewrite a memory shared by all. But it also requires the need to establish positive relationships with each other, leave fear and mistrust behind, and share common visions of the future in order to build a fair and equitable society.

This new monograph for Peace in Progress explores processes of reconciliation through a theoretical framework, lucidly provided by University of Ulster professor Brandon Hamber, and through the analysis of specific cases, such as those of South Africa, Bosnia, Sri Lanka and Colombia.

In the case of South Africa, in a society that is still divided today and with high levels of inequality, we focus on what South Africans think about the reconciliation process they have experienced and on the results of the Truth Commission. We do this based on data extracted from the barometer of South African reconciliation, in an article by Jan Hofmeyr and Elnari Potgieter, researchers at South Africa’s Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

We explore processes of reconciliation through a theoretical framework and through the analysis of the cases of South Africa, Sri Lanka, Bosnia and Colombia

We analyze the case of Sri Lanka, where the violent conflict lasted more than thirty years, in an article by Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, of the Institute of National Security Studies of Sri Lanka. The article sets forth the will of the current government to strengthen social cohesion strategies, but also the limitations on the path to reconciliation: the lack of a global vision and the isolation of the country, which makes it more difficult to face this challenge.

We also wanted to look at the emblematic case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where 26 years after the signing of the Dayton Accords, reconciliation today still seems impossible, as Daniel Eror, president of Youth for Peace, maintains in his article.

Finally, we wanted to include two cases from Latin America. The first case is addressed in an article that focuses on indigenous peoples, who have been the victims of serious human rights violations in countries such as Guatemala and Colombia. To what extent does transitional justice adapt to the worldviews, norms and practices of indigenous peoples? A Colombian lawyer, Belkis Izquierdo, and a Belgian researcher, Lieselotte Viaene, provide insight into indigenous peoples’ views of reparation, justice and reconciliation and raise intriguing doubts about an excessively westernized form of justice.

The analysis of post-conflict societies is one of ICIP’s priority strands of work

And secondly, the Interview section focuses on the Colombian conflict, specifically on the successful experience of coexistence and reconciliation in the small municipality of San Carlos, in the department of Antioquia. We speak with Pastora Mira, victim of the conflict and coordinator of the Center for Rapprochement, Reconciliation and Reparation, which has promoted coexistence between victims and victimizers.

This monograph has been produced coinciding with the international seminar “Experiences of reconciliation,” which ICIP organized in May in collaboration with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Foundation, and is part of the new action program “Peacebuilding and the construction of coexistence after violence,” with which ICIP aims to promote work in post-conflict contexts.

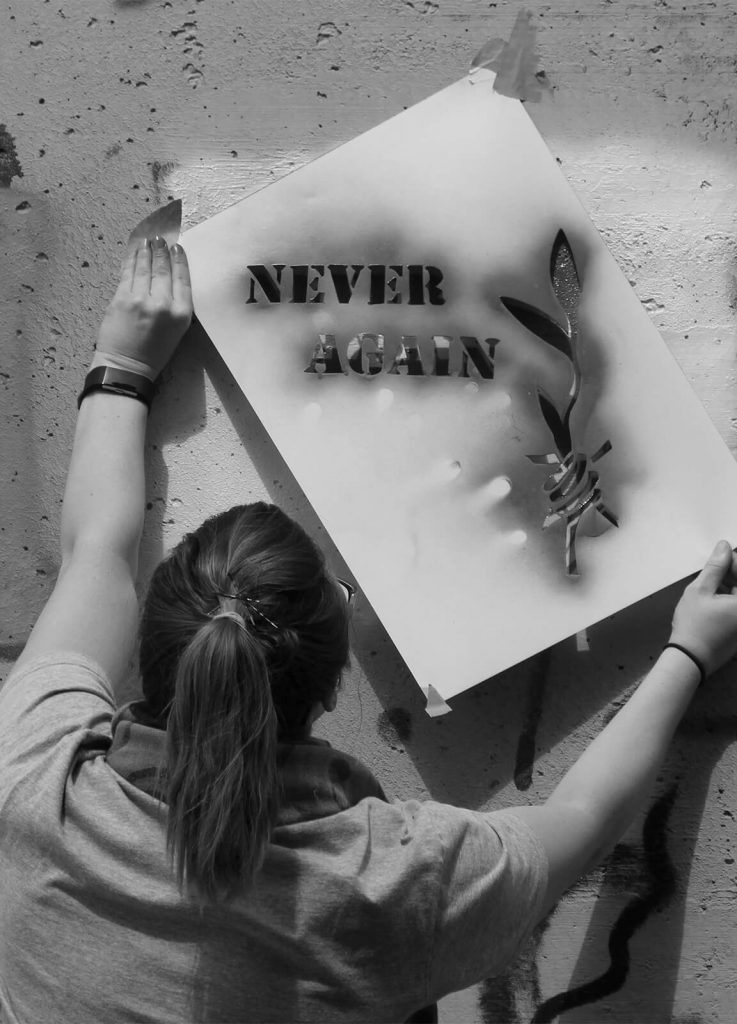

Photography : Graffiti on the Apartheid Wall, Bethlehem

© Generalitat de Catalunya