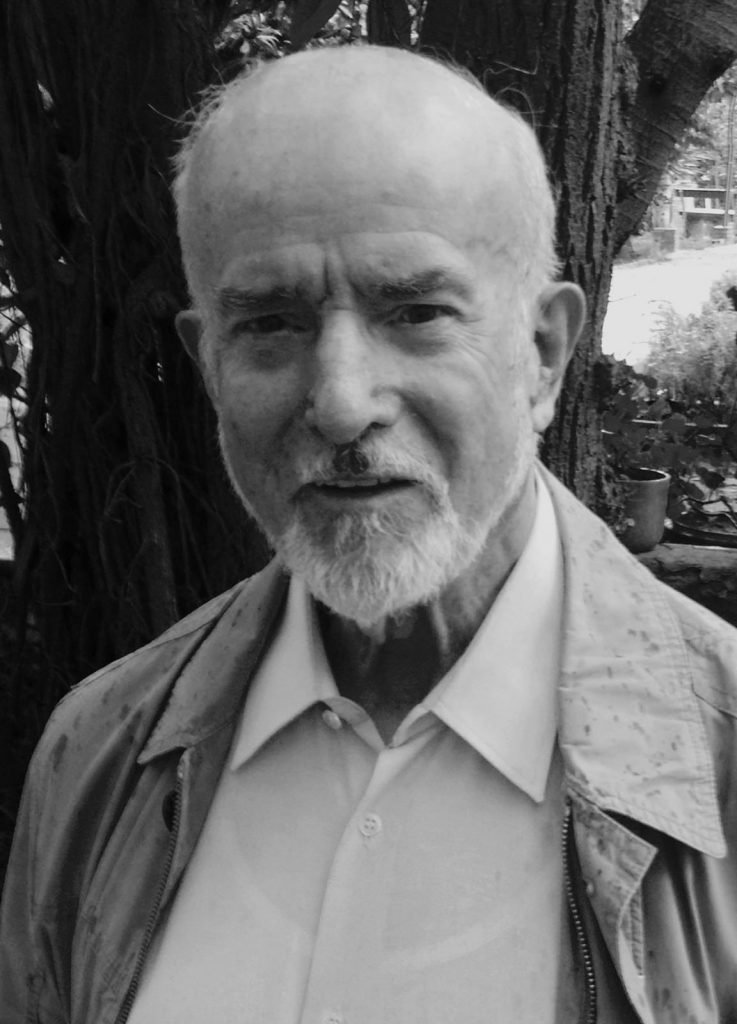

Joan Botam, Catalan priest and Capuchin friar

In the First World War, at least three branches of international pacifism could be found. The first one, scientific or realistic pacifism (which we analyze with d’Alfred Fried), was characterized by the belief that peace could only be guaranteed with world organization and scientific research. The second one, feminist pacifism (which we have dealt with in this article), was represented by women who associated their subjugation with militarism and military spending. The third one is the religious pacifism of Quakers, Mennonites or Tolstoyans. We will be talking about this branch of pacifism in this interview with the Catalan priest and Capuchin friar Joan Botam, who has launched numerous initiatives linked to peace and ecumenism.

Botam (Les Borges Blanques, 1926) is a doctor in theology and founder of the Víctor Seix Institute of Polemology and of the Ecumenical Center of Catalonia. He represented Barcelona at the United Nations Millennium Summit of religious and spiritual leaders.

To understand religious pacifism during the First World War, one of the fundamental groups one must look at is that of the Quakers. What are their characteristics?

The Quakers are staunchly nonviolent pacifists, with a spirituality of a personal nature, without borders. The term “Quaker” come from the verb “to quake.” Their human and faith experience is so sensitive that when they engage in communication, projection or dialog, they “quake” because they are aware of the infiniteness of God, of the absoluteness of God. It’s the creature before the Creator, limitation before absoluteness. And they have had this sensation since their origins in England, in the 17th century, with George Fox, their founder.

With the outbreak of war, the pacifist movement FOR (Fellowship of Reconciliation) was created in 1914 at the initiative of two Christians, Henry Hodgkin (an English Quaker) and Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze (a German Lutheran). You have known people associated with this movement. What is the philosophy behind it?

FOR –later IFOR- is a movement of reconciliation that is heir to an exceptional pacifist like Jean Goss-Mayr. I knew him and his wife Hildegard, who was the daughter of an Austrian pacifist [Kaspar Mayr, founder of the Austrian branch of IFOR]. Jean Goss was a French railway worker, a charismatic man with a great amount of energy and conviction. He maintained –as do I- that violence is one of the greatest absurdities. It’s an absurdity and also a sin because everything that is an imposition does not respect or take into account the other. It manipulates subordinates and kills the other.

You didn’t live through the First World War, yet you have a long-standing relationship with pacifism. When did it start?

I come from the pacifist movements of the 1950s and 60s. In fact, my story begins with the Second World War, with the founding of Pax Christi, a pacifist movement of people of all creeds, united by Nazi persecution. In 1956 I was called to serve as a counselor to the movement and I started to play a prominent role. Pax Christi was a religious movement, but free, not institutional or hierarchical. It wasn’t Catholic from the top but from the grassroots, and with a clear purpose to form citizens, members of the international community, on a solid foundation of democracy and freedom.

I am anti-war, anti-military and anti-weapons because I believe that the world is built from good, truth and justice, by peaceful means

What does being a pacifist mean to you?

I am anti-war, anti-military and anti-weapons. Because I believe, from Gandhian philosophy and from the mystical thought of Martin Luther King and also from the Gospel, that the world is built from good, truth and justice, by peaceful means. Those who use non-peaceful means, such as war, to build peace fall into a flagrant contradiction!

How did experiencing war affect your personal thinking?

I experienced war personally. I was a teenager in 1936 when bombs fell on my town. I had been taught in public school about what to do in the case of bombing and, while it was being explained to you, it sounded like heavenly music, but darn! When, on April 2, 1937, I looked up at the sky –a bright sky like today- and I saw advancing planes that suddenly started giving off flashes of light, sparks that whistled as they came down… and then I heard crackling sounds amid a cloud of dust, and screaming and yelling. I was 9 or 10 years old and that stayed with me. It was negation, death, hell. And I heard women yelling “Stop this! Stop the war!” I carry that cry inside of me, almost like an anthropological constituent element.

Is it also war that leads you to religion?

For me, until 1939, there was zero religion. That year I was forced to make my First Holy Communion dressed up as a little Falangist, with cannons and machine guns by my side. That was all the religious instruction I had had until then. But from 1939, since there was no school, my father –a Republican, anti-clerical believer, as I would have been because there was no other honest alternative- took me to the Capuchins of Les Borges. The very next day after Franco’s troops had marched through, the Capuchins opened their doors.

Religions are not always a source of peace. The Church as an institution sometimes feels it has power. And power kills.

What did studying in the convent of the Capuchins mean to you?

It was a shock from the point of view of the environment, education, methodology, seriousness, work and determination. I was above average and proof of that is that in 1942, after three years, I was at the top of the school. I underwent a process of self-renovation, an educational process: to bring out what you have inside of you with the means at your disposal. And thanks to the beautiful human relationships I found between students and teachers, the belief element also emerged. It was not an ideological, conceptual or philosophical process. But it was the beginning of a vocation with which I’m not dissatisfied, quite the opposite: I have found “meaning,” that which is self-satisfying, which makes you feel useful and helpful.

Considering your knowledge of different spiritualities, do you believe that religion is always a source of peace?

No. Because religion –not faith- as an institution and as an organization tries to institutionalize and normalize a human, spiritual and divine experience. It tries to explain things that are inexplicable, such as the supernatural experience of the absoluteness of God. I’m not saying that religions are useless, but the Church should always serve and research with care. But sometimes it feels it has power. And power kills.

In your opinion, can there be a contradiction between the Church as an institution and as spirituality?

Certainly, because there is the Vatican State, Papal States, media and economic potentialities like Opus Dei… and this is in total contradiction with belief and spirituality. There is a theologian that I greatly admire, Karl Barth, who says that religion explained in this way is a sin.

And do you agree with that?

Yes. It is a religion that does not question itself, does not challenge itself, does not know its place and often creates obstacles. The Inquisition, for example, is an obstacle. How can you burn at the stake someone who believes differently? Now that doesn’t mean that peace cannot be built from religion because the vocation of a Christian is precisely to build peace. And building peace means collaborating and talking to everyone, without adjectives. Peace is peace and it is the peace of everyone. Limits cannot be placed on dialog; one must talk to everyone, even to the devil if necessary!

Building peace means collaborating and talking to everyone, without adjectives or limits

What role does ecumenism play here?

Outside the Christian world, there are other groups that link ecumenism and peace, like the Baha’i faith. Do you know them?

Outside the Christian world, there are other groups that link ecumenism and peace, like the Baha’i faith. Do you know them?

Yes, I have Baha’i friends. Baha’is originated in Iran, in conditions of persecution, and they represent an attempt at ecumenism from an Islamic root. They belong to a movement of spirituality –not a religion- according to which God is everyone’s father, humanity is one single family and our work is peace and dialog. There are also the Brahma Kumaris, for example, who are similar but of Hindu origin, with a universal vocation of fraternity and nonviolence.

Taking into account the conflicts and wars of the 20th century, do you think that religious pacifism has fought enough to build peace?

No. One gets the impression that many still don’t believe in it. People like Jean Goss, Lanza del Vasto, Lluís Maria Xirinacs or Martin Luther King are hard to find. I am spiritually radicalized in that respect, in the struggle for peace, but it is hard to create a culture of peace and relationships based on the building of peace. It is difficult to make people conceive that reconciliation and peace are above one’s own interests.

© Generalitat de Catalunya