Roberta Bacic, human rights researcher and collector of arpilleras

Roberta Bacic, born in Chile and resident of Northern Ireland, is the founder of Conflict Textiles, an international collection of arpilleras very significant in the world. She holds a philosophy and English teaching degree and works as researcher in fields linked with human rights. During the period of Chilean dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, Bacic dives into the world of arpilleras. The use of textile artisanship allows her to denounce the repression and violence from which the Chilean people, especially women, suffer. At a later stage, she will use her collection to export this language to other countries, also Catalonia.

Arpilleras constitute an artistic way of protest, political resistance, therapy, social participation… How and why are they created?

Arpilleras saw the light in Chile during the seventies as the result of a growing need for women who were direct victims of political repression to express themselves; women whose husbands, partners, children or parents had been arrested, had disappeared, been tortured, imprisoned or were living in exile. In this context, two phenomena emerged: on one hand, the need for these women to act against the events, to denounce, to be able to be the main character of their own story; and on the other hand, the need to survive, because they became the key person in the maintenance of their families. In fact, as off the year 73 –after the military coup- women who, until then, often stayed home to look after their children, had to fulfil a double role: that of a mother who had to provide, and that of a wife who was looking for her missing relatives. This is how the arpilleras workshops, the way we know them now, started.

Does this mean they didn’t exist before?

Some textile works existed, like the ones of the famous Chilean folklorist Violeta Parra, but technically, they were completely different. Violeta Parra’s arpilleras are bigger and embroidered, and deal with social issues, while the ones I collect are produced with bits of used material, like for example the cloth from these same women’s skirts. Moreover, the embroidery is an additional element, used to join the pieces, but it is not the central one.

Your arpilleras focus on the protest against political repression?

The ones I produce, yes. But they also want to tell a story about daily life through political actions. For example, there is an arpillera called “Corte de agua” (Water cut) that demonstrates the women’s ability to organise themselves when confronted with water cuts which are the result of political repression. In this situation, women represent their daily life and how the circumstances that surround him have changed it.

Arpilleras saw the light in Chile as the result of a growing need for women who were direct victims of political repression to express themselves

Has the arpillera technique also become an element of empowerment for women?

The arpilleras have been an instrument of empowerment, but also of protest, testimony and preservation of memory. It is not simply a technique, I prefer to talk about them as a language, because some arpilleras are made with very little technique, by women who hardly knew anything about stitching, but their art lies in how they manage to communicate what they want to tell. It is the language used to transmit these women’s entire life, with its political and social load. As Primo Levi said, when someone goes through extreme situations, as there are the concentration camps, words are not enough to describe these experiences and new forms of communication need to be found. And one of these forms is the textile artisanship, where a woman can continue working in her house, and while she sews, she is using the time bank: the reflection time and the clock time.

Is this language exclusively reserved for women?

I would say it is mainly used by women. Men have found other ways to testify of what they have gone through (for example, from inside prison) and in some –African- cultures, it is precisely men who produce textiles while women work on the land. But the big majority of Chilean arpilleras have been made by women, which is why they relate on how acts of violence have interrupted their daily life and show the pain from the loss or disappearance of their husbands, partners or children. This is how these women become the authors of their own story, claim authorship of their own life and become self-empowered to take up a dynamic and active role.

How did the first women organise their sewing activities?

During the Chilean military dictatorship, the majority of the workshops were supported and facilitated by the Chilean Catholic Church through the supply of physical space and material for the development of the workshops, after which the textiles were exported by the Fundación Solidaridad (Solidarity Foundation). This represented a massive export of arpilleras, thousands of them were shipped abroad in times of silence. At first, they were ignored, since they were considered simple textiles, made by women. But later, when their true value was discovered, the arpilleras were prohibited and considered subversive for many years.

The arpilleras have been an instrument of empowerment, but also of protest, testimony and preservation of memory

How did they evolve since then?

In many different ways. For example, nowadays, arpilleras are also used as a part of art-therapy, in order to process traumas, mostly for women who went through situations of domestic or sexual violence. They have also been used together with other objectives of protest than the political ones, they have been produced in schools and used as a technique to recover informal testimonies of unlawful acts.

The technique was born in Chile, but has also been applied in many other countries. Where did it get the biggest repercussion?

Most of the works that have been produced in other places were created based on exhibitions that we organised by Conflict Textiles. Other women have discovered the need to express themselves using this language. For example, in Northern Ireland, where I have been living and where conflict is alive and kicking, women have started to tell about what happened in their communities, using arpilleras. Also in Catalonia, where I first exhibited in 2008, the women of the Ateneu of Sant Roc, in Badalona, organise arpilleras workshops around the Spanish civil war, and precisely this autumn, you can visit the show “Arpilleras en acció: Refugiats” (Arpilleras in action: Refugees). Also in the Basque country, Argentina, England… arpilleras are being exhibit as a language and conversation form through textile material, and all of them constitute spaces where women can tell their own stories.

It is the language used to transmit these women’s daily life, with a political and social load

How do you manage to direct the biggest collection of arpilleras in the world?

I am Chilean, I lived in Chile throughout the entire period of military dictatorship, and I have been around arpilleras since 1975. They have become an inherent part of my life, but it has only been when I arrived in Northern Ireland that I was asked to find new methods to work with communities, opposed by conflict, which is when I started using arpilleras as a resource. At that moment, I rediscovered textiles I had bought and been given as a present, and I started a collection. More and more came in, also through donations, and now the collection Conflict Textiles contains more than 300 documented pieces. It is the completest existing archive worldwide, an archive I call “dialoguing”, because it is not just textile, it can also be used for exhibitions, conferences, book covers, etc. and it can interact with some associated activities.

Out of your extensive collection, there is one arpillera you feel especially connected with: the Arpillera Peruana, which illustrates the violence, experienced by the women affected by the conflict between the Peruvian government and the Shining Path organisation. What does it represent to you?

This arpillera, called “Ayer y hoy. Las mujeres de Kuyanakuy” (Yesterday and today. The women from Kuyanakuy), which now is kept in Peru’s memory museum (“Lugar de la Memoria, la Tolerancia y la Inclusión Social”) had a big impact on me since I used it to illustrate how the conflict in Northern Ireland could be addressed. I borrowed it from my colleague Gaby Franger, co-founder of Women in One World. It shows how women, affected by the conflict on both sides, have more things in common than they have differences. All women, on one side as well as the other, were poor, displaced, had lost husbands and children… they were more united than divided by the situation. It is a way of saying we need to look for what brings us together, because divisions only feed traumas.

This is a good example of how artistic expressions can contribute to the peacebuilding process.

Exactly, and this contribution is made by taking up a proactive role in the creation of spaces of empowerment where human rights violations are put on display. Peacebuilding is based on the ability to address the issues that interrupted our lives. For example, the arpilleras have helped women learning how to live with the pain they will never be able to forget. Someone who lost a child cannot forget. A truth commission is important at the social level, but how can we strengthen the aspects of life that help us to move on? This is where community work and the reinforcement of community ties become important, because whatever happens to one person, also happens to others.

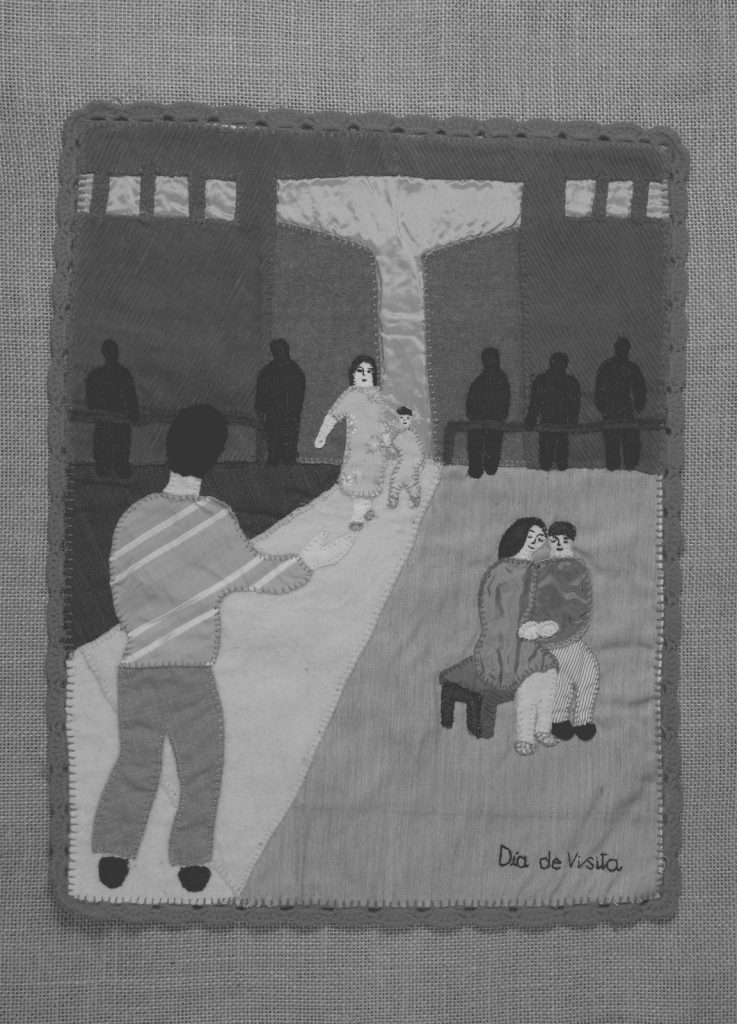

Photography : Martin Melaugh. “Día de Visita / Day of Visit”, by Victoria Diaz Caro.

© Generalitat de Catalunya