Boban Minic, the Radio Sarajevo journalist who refused to leave the Bosnian capital during the war, says that the world is divided into two kinds of people: those who have lived through war and those who haven’t. And, he adds, there is yet another classification: those who had never left their city until, one day, they emigrated.

There may be empathy, solidarity, understanding, a desire to help… -fortunately, there is a lot of all that, even though it doesn’t make the headlines-. But it is difficult to put oneself in a refugee’s shoes. Trying to imagine how someone must feel after losing almost everything. Home, work, family, friends… a safety net which – like those of us here today – they thought would always be there. The only thing they drag along with them is the backpack of defeat, fear, the uncertainty of exile, the weight of broken dreams. They have lost everything except life… and the strength to keep on going. They are driven by a firm decision: they do not give up; they are willing to start over again, from scratch. Some do it for their children; others, to resume their studies, to keep a cause alive… or simply out of an instinct for survival. Everyone has their own reason for not throwing in the towel and this is what accompanies them on a journey that becomes somewhat of a Darwinian obstacle course where only the strongest survive: those that are more capable of adapting to an increasingly hostile environment.

In the makeshift refugee camp in Idomeni, Greece, the Syrian Arab refugees elected a committee of twelve men and women to coordinate protests (there were small handwritten signs everywhere calling people to demonstrate two or three times a week) and negotiate with the Greek and Macedonian authorities. “Merkel said that all the Syrian refugees would be resettled in Germany and, when we were halfway there, they blocked our way. The European governments are the ones who have put us in this situation,” El Mahdi, one of their members, reminded me. A cook from Aleppo, his eyes were stinging from the tear gas fired at them by the Macedonian army. Family, neighborhood, community and friendship ties become real lifesavers in extreme situations and they are the first tool for solidarity that serves as a refuge, weak but essential. Teachers (Syrians, Iraqis and Kurds) volunteer at “schools” improvised by charitable organizations. They are parents who kill time making toys or barbecues out of pieces of wire fencing (made in Spain, by the way: Melilla has proven useful to test many things). They are grandchildren who push grandparents in wheelchairs for thousands of kilometers. They are the friends of Mustafa, a young man from Deir el Zor (in eastern Syria) who lost his left leg in an attack three years ago, who have not abandoned him for a single moment on his journey through Syria, Turkey, Lesbos and Athens, until he reached Idomeni, where the door was slammed in his face. And they still have enough strength to get excited about FC Barcelona games and can recite the following Sunday’s lineup by heart. “I’m slow, but I’m patient… and there is always someone who helps me,” said the young Syrian student of English philology, leaning on his crutches, 2 700 kilometers from home.

There is a great contrast between the reaction from below and the policies of governments that have done nothing but build walls and fences, militarize the streets, and fill the Mediterranean with warships

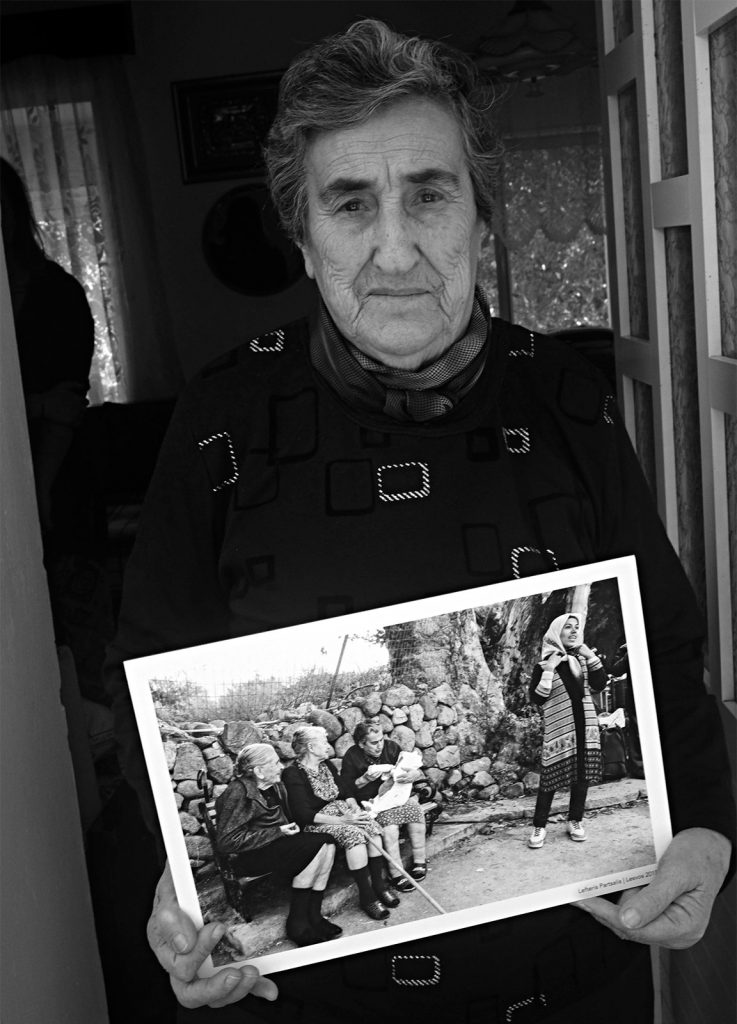

The second ring of solidarity is formed by the people in the trenches, on the front line of arrival. People like Emilia Kamvisi, who, at 84 and with a pension of less than 400 euros, would go down to the beach in front of her house on the Greek island of Lesbos every day to help people that had been transported in dinghies from Turkey: “Seeing how they arrived made us very sad and very angry: scared, wet, with children who were soaking wet and crying. Every day we went down to the bench on the beach to sit with them, to keep them company. Six, seven, eight boats would arrive: we couldn’t speak but we embraced and kissed,” she explained a few months ago. And she remembered her mother, who had also arrived as a refugee after the expulsion of Greeks from Turkey in the 1920s. The Nobel Peace Prize passed the candidacy of the people of Lesbos by, which symbolized this welcoming spirit. But we will always have Lefteris Partsalis’s photograph, which went viral, where Emilia –sitting on that same old bench facing the sea – is bottle-feeding a newly arrived baby in the presence of the infant’s mother, who is smiling broadly. The grandmother, with her two friends and the fishermen on the island, gave faces to the thousands of young people, workers, and others who went out on a limb to rescue shipwreck survivors: to heal them; to embrace them; to provide them with dry clothing, a cup of hot tea, food, water, and transport; or simply just to listen to them.

It is the states which have painted refugees as a threat to our security and coexistence, and it is the states which are responsible for a suffering that is absurd and entirely avoidable

The third ring consists of the international mobilization of volunteers and NGO personnel, who have been leaving destinations in Africa, the Middle East and Asia for cities and towns that are closer to home. It hasn’t been easy and many things can be criticized, but the most important thing is the contrast of this reaction from below with the policies of governments that have done nothing but build walls and fences, militarize the streets and fill the Mediterranean with warships.

We must not forget that, in fact, solidarity was the initial reaction last summer, even in countries like Austria, where subsequently the extreme right has grown strong. Because it is government policies, criminalization, the explosive cocktail of immigration-Islam-terrorism that have deluded a sector of public opinion in Europe and have fueled extremist speeches which now resound uninhibited in parts of the continent. It is the states which have painted refugees as a threat to our security and coexistence. And they are responsible, in the first instance, for a suffering that is absurd and entirely avoidable, that leads us all into a spiral of hate. Faced with this situation, we can only advocate solidarity and ask ourselves whether, deep down, the walls that are being erected are also imprisoning us.

Photography : Emilia Kamvisi, at her house in Lesbos, holding the picture that turned her into an icon of solidarity with the refugees. XAVIER BERTRAL / ARA

© Generalitat de Catalunya