Religious war, ethnic cleansing, a country about to be torn in two… The media deals with the crisis in the Central African Republic (CAR) in these terms. And, even though it is undeniable that religious massacres have been perpetrated in these past months, reducing the conflict there to religious terms is a simplifying vision that hides other essential aspects of the problem. This bipolarization has distracted the attention of the world from the origins and instigators of the Central African drama, those responsible for thousands of deaths that will sadly escape without trial.

Where should we start to explain what is happening now in the Central African Republic? Before this conflict, hardly anybody even knew that the country existed.

In the mid-20th century, the territory of Ubangui-Chari was part of French Equatorial Africa and the congressman Barthélemy Boganda was its representative in the French National Assembly. Boganda decided to found the Central African Republic, which he proclaimed on the 1st of December 1958. But he died in a mysterious plane accident on the 29th of March 1959. David Dacko succeeded him as the head of the RCA, obtaining the country’s independence on the 13th of August 1960.

Soon after that, this small country started to get attention from the media due to the rise to power of Jean-Bedel Bokassa. A former officer of the French Army, Bokassa had returned to his native country to form the national army. In the night from the 31st of December 1965 to January the 1st 1966, he gave what became known as the coup d’état of Saint Sylvester. Once he became president he was initially France’s protégé, being even allowed to crown himself as the Emperor of the Central African Empire. But Bokassa started to become increasingly a nuisance, due to his multiple extravagances. He was finally deposed in the Operation Barracuda of the French Army, on the 21st of September 1979. David Dacko was once again put at the head of the Central African Republic, but he wasn’t able to lead the country out of the crisis and he was forced to give the power back to the army on September 1981.

General André Kolingba, aided by the Military Committee for the National Recovery, became the man in power. He created the only legal party (his own, obviously): the Central African Democratic Rally. A decade of calm followed, with the country receiving thousands of refugees fleeing from neighbouring Chard, torn by a long civil war. There were close ties between the two countries, and Centro African citizens from the north would mix with the Chadians from the south. The Chadian merchants started to become a key element in the economy of the Central African Republic.

André Kolingba was one of the heads of state that was not able to elude the 1990 discourse of François Mitterrand, La Baule 1990. Submitted to the road map set by the French president —multiparty, democracy, elections—Kolingba lost the 1993 elections, in which Ange Felix Patassé was elected as the president of the Republic.

Reducing the conflict to religious terms is a simplifying vision that hides other essential aspects of the problem

The start of the conflict

As soon as he became president, Patassé insisted on revising all the country’s foreign agreements, even the Defence ones with France. But the Barracuda (name given to the French military after the operation Barracuda) had large bases in the CAR and they participated in the fight against poachers and road robbers who had come from the Sahel and the Sudan.

The real problems started then. The CAR is a country with an extension of 623.000 km2, with a population of 4.5 million and with very desirable riches under its surface. The French Military, who had looked out for the security of the country, left for Chad and Patassé had an army of 2.000 soldiers, most of them still loyal to the deposed general. Under Patassé’s regime there were several uprisings, two failed coupes d’état and finally, a successful one on the 15th of March 2003, led by François Bozizé, Patassé’s former Army Chief, who had Chad’s support. Thirteen years before that, on the 1st of December 1990, Idriss Déby had led a successful coup d’état against Hissein Habré in neighbouring Chad.

During the army mutinies, under Patasse’s regime, the Central Africans got to know the MISAB (Mission Monitoring the Bangui agreements), that became the MINURCA (United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic), which finally decided to leave the country.

Bozizé, the Seleka and the anti-Balaka

François Bozizé created his own political party (KNK) and he organized elections in 2005, two years after his coup d’état. Despite his incapacity to lead the country to stability, he won those elections and the following ones on the 23rd of January 2011.

In order to obtain power, Bozizé had used “Zakawa” mercenaries from Chad who lived in the Central African Republic. Instead of paying them and ridding the country of these outlaws willing to shoot at the slightest provocation, he kept them with him and incorporated many of them into the national army. His personal guard was also formed by these same elements that had been fighting in Chad for long periods of time. They had more in common with the Chadian traders and other Central Africans of Chadian origin and they often committed abuses against the other part of the population. Frustration led to an increase in tensions between the two communities.

In his ten years in power Bozizé’s policy was basically to stay in power thanks to foreign armed forces. He did not fulfil his promise of restructuring the army and he never made it a Republican Army. After a rift with Idriss Déby and having lost France’s support, Bozizé asked Jacob Zuma and the South African Army for support. His aim was to exploit the petrol that was in the same basin as Chad’s. He also allied himself with China and gave to India the control of the cement production.

And then came the Seleka! Michel Djotodja, Nourradine Ahmat, Mohamed Daffane and other warlords who had helped Bozizé achieve power now wanted their piece of the cake. The words of Abakar Sabone in the process of political dialogue initiated by François Bozizé still resound today: «The Christians have been directing this country for 50 years and the results are catastrophic. They have failed, a Muslim must be given the opportunity to take the reigns of the country.»

It is not a religious war that’s going on in the CAR, it is two sides trying to find the necessary support to retake or keep power

Seleka- Islamic rebel forces- found their perfect ally: the marginalized Muslim minority. Djotodja used the support of the Islamists to gain power by arms and, once he reached it, proved incapable of imposing rule of law – as had proved all previous Central African governments. Quite the contrary; during his nine months in power, Seleka committed abuses of power over the civil population, and Michael Djotodja was forced to resign by the international community.

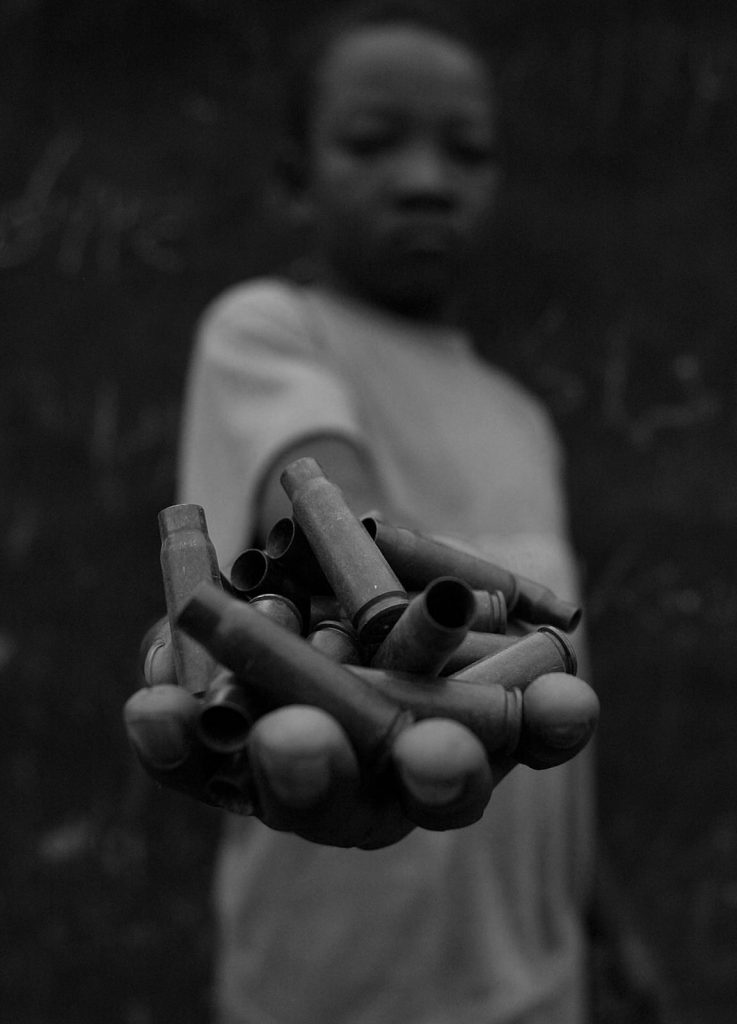

The anti-Balaka had their origin in a group of self-defence –formed years before the Seleka arrived- by the inhabitants of the villages in order to protect their scarce properties from the bandits known as Zaraguinas. As things got worse, with the abuses committed by the members of the Seleka, who burned their villages, raped their daughters, etc. they became more radicalized, in order to confront their attackers with rudimentary weapons. Finally, this self-defence group was adopted by the entourage of Bozizé’s old regime and transformed into a systematic murderer of Muslims. They adopt the strategy of the warlords: Leading the non-Muslims to believe that the Islamists want to take control of the country by force and that they must fight to expel them.

A religious war?

Bozizé got rid of Patassé with the help of soldiers from Chad and now Djotodja did the same thing to him, sending him to neighbouring Cameroon. It was then that Bozizé went all-out: he wants to return whatever the cost. In fact, he only wants two things: to recover power and discharge all the hate he feels towards those who deprived him of it. To achieve this, he will stop at nothing. Bozizé and Seleka are not fighting for Muslims or Christians, only for power. In the Central African Republic there are atheists, animists, etc. You can, after all, be a non-Muslim without being a Christian. It is not a religious war that’s going on in the CAR, it is two sides trying to find the necessary support to retake or keep power. Before being deposed by Bozizé with Chad’s support and France’s blessing, Patassé signed a contract ceding exploitation rights to the country’s petroleum with Jack Grynberg, the owner of RSM Petroleum. This contract expired on the 23rd of November 2004. Bozizé had to renegotiate it but he decided to up the ante and sell the oil to the highest bidder. There was also the contract for the exploitation of the uranium in Bakouma. This is a very complex matter, very difficult to summarize in just a few lines. As in so many other aspects, the ones paying the highest price are the French and the Central Africans. The French Government paid 1.800 million euros from taxpayer’s money to buy the Bakouma mines that were then owned by the Canadian company Uramin. But then Bozizé’s government considered that the agreement between AREVA and Uramin was treacherous. Matters went to court and it was then that the mayor of Levallois Perret, Patrice Balkani, intervened, after allegedly having earned 5 million dollars as his commission for mediating in the negotiations.

Nowadays, despite the embargo put in place by the Kimberly Process, the militias continue to exploit the diamond and gold mines in the areas under their control. They move these stones to other countries and they are, through them, able to sell them. The militias are still heavily armed and they keep the population hostage. Many Central Africans barely survive in refugee camps in the capital while others, in the interior of the country, have fled from the hostilities and live like animals in the savannah, waiting desperately for the disarmament to come and with it a return to normality and to their homes. Meanwhile, the warlords, other than having been admonished and threatened with having their assets in France frozen, enjoy full liberty and run free through various African countries. These people continue to arm, finance and motivate people to commit massacres, using them only as an instrument of pressure in order to keep on running the country or to recuperate power.

Photography : hdptcar / CC BY / Desaturated.

© Generalitat de Catalunya