After a period of extreme and systematic violence characteristic of dictatorial or authoritarian regimes, armed conflicts and civil wars, and characterized by serious violations of human rights and of international humanitarian law, many societies claim that states have a political and moral duty to provide information and activate mechanisms to clarify the truth of the events and those responsible, and the corresponding obligation to guarantee non-recurrence of violent acts through the construction of a narrative thread and subsequent reparation for victims. Additionally, victims must be recognized as subjects with rights and given a voice to transmit to the rest of society what the events were and the magnitude thereof.

Clarification of the truth is one of the demands that victims share and, in this transitional justice framework, the establishment of a Truth Commission can respond to this need to cope with a painful past and activate the beginning of a long process of reestablishment of the rule of law, on the road to reconciliation, in societies fragmented by violence.

Truth Commissions have become a powerful tool to investigate serious human rights violations and there is currently a legacy of over 40 commissions worldwide. They are set up as officially authorized investigative bodies that are temporary and non-judicial. These commissions have a predetermined period of time to take statements, conduct investigations through testimonies and the compilation of documents, and hold public or private hearings before finalizing the process with the publication of a report. Although they are not structured as a substitute for judicial action, they offer a possibility to explain the past and reduce a possible loophole of impunity since the resulting reports can be used for subsequent prosecutions, reparation processes and to undertake institutional reform.

The establishment of a Truth Commission can respond to need to cope with a painful past and activate the beginning of a long process of reestablishment and reconciliation

However, Truth Commissions are also instruments of transitional justice that are tinged with significant weaknesses and challenges and that often presuppose ambitious goals that can call into question their effectiveness as peacebuilding tools. The ongoing debate on how to reconcile peace and justice and, in the end, how to hold those who have committed crimes and human rights violations accountable, is one of these controversies that demonstrate how Truth Commissions can be created with strong limitations on their actual scope.

To reflect on some of these issues we present a new monograph in the e-magazine Peace in Progress. In the first article researcher Cath Collins questions the very idea of truth and looks into what its specific social purpose is. In this regard, she stresses the importance of defining the limits of what is considered the narrative of truth in order to avoid a war of words and meanings, and to make of this narrative a real opportunity for new paths of peace.

Additionally, with the aim of looking into the real impact of Truth Commissions, Carlos Fernández Torné wrote the second article, where he reviews the academic literature that has evaluated, both quantitatively and qualitatively, the consequences of commissions by means of performance indicators in terms of democracy and human rights. The researcher explains that the evaluation must be done through the analysis of the process, of government accountability, since it is necessary for the state apparatus to display a genuine openness that will enable a greater sensitivity toward the demands of civil society, in general, and toward those of the victims, in particular.

Truth Commissions are also tinged with weaknesses and challenges due to the ongoing debate on how to reconcile peace and justice

However, sometimes the search for truth fails to materialize and is reduced to an unmet need for victims and their relatives when government agencies explicitly refuse to investigate the crimes committed. This is the case of Spain, as set forth by Jaime Ruiz, president of the Platform for a Truth Commission on the Crimes of the Franco Regime. The articles that follow look at the development of two very different cases. First, lawyer and human rights consultant Alejandro Valencia comments on the challenges posed by the composition, structuring and functioning of the recently created Truth Commission in Colombia, provided for in the peace agreement between the government and the FARC that was signed last autumn. Then, journalist Ricard Gonzalez presents the contributions that Tunisia’s current Truth and Dignity Commission has made to the doctrine of transitional justice. At the same time, though, he also describes an uncertain scenario regarding the fulfillment of the ambitious goals that were initially set.

Finally, in an interview, we discover the view of human rights activist Helen Mack with regard to what the Truth Commission of Guatemala has meant for the victims of the conflict. Her testimony brings us closer to the struggle of thousands of people around the world who are suffering secondary victimization by an unchanging state model that has failed to provide needed reparation and that, on the contrary, has consistently ignored them.

This monograph seeks to offer a variety of perspectives regarding the use, limitations and opportunities of truth commissions through the eyes of people with different personal and professional backgrounds who have analyzed and become acquainted with contexts or commissions that have unique characteristics. It is for this reason that the collection of articles aims to become a tool for reflection on the ability of truth commissions to transform a conflict; clarify past events; recognize responsibilities; rebuild confidence in state structures; work in favor of forgiveness, reconciliation and peaceful coexistence; and advance toward the fairest and most effective option in response to the voices and countries that demand it.

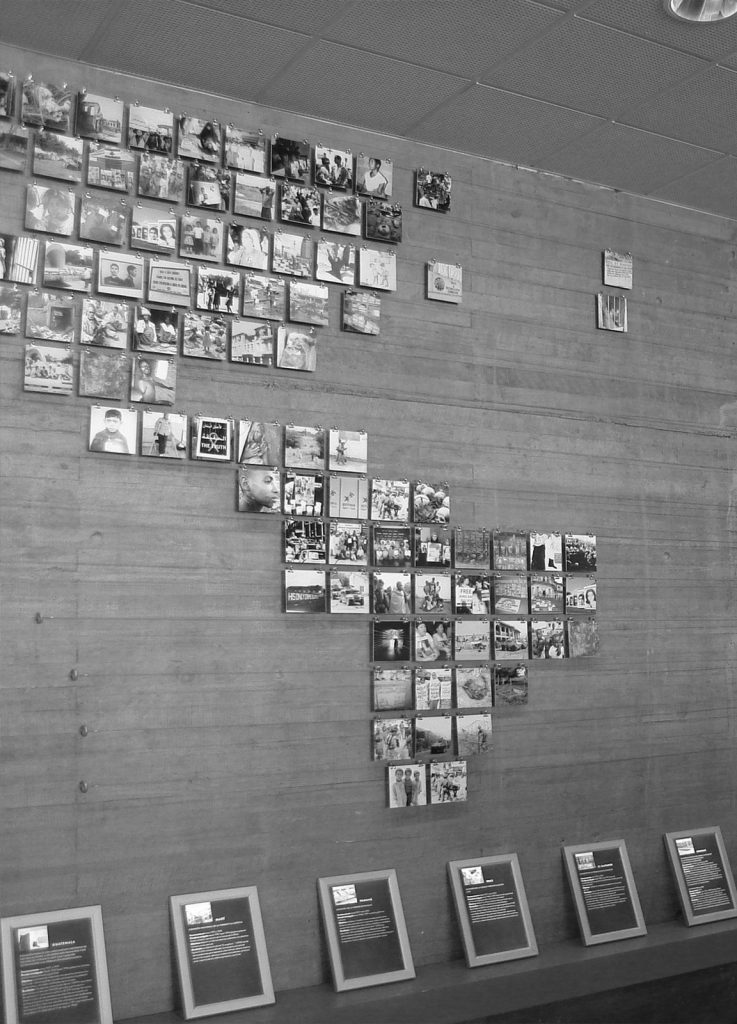

Photography : Warko

© Generalitat de Catalunya