On March 15, 2016, over three hundred grassroots peacebuilders gathered in the public plaza of El Carmen de Bolívar, Colombia. As democratically-elected representatives of afrodescendent, indigenous, feminist, LGBTQ, and youth movements, these social leaders came together with state authorities, private sector actors, and representatives from local NGOs to “sign peace” in Montes de María – one of the territories most affected by the internal armed conflict in Colombia. The symbolic political action was organized by a broad-based coalition, the Espacio Regional de Construcción de Paz de Montes de María. With news that the formal, peace negotiations between the government of Colombia and the FARC were faltering in Havana, Cuba, the symbolic “peace signing” in Montes de María generated widespread national and international attention and garnered support for the fragile peace negotiations.

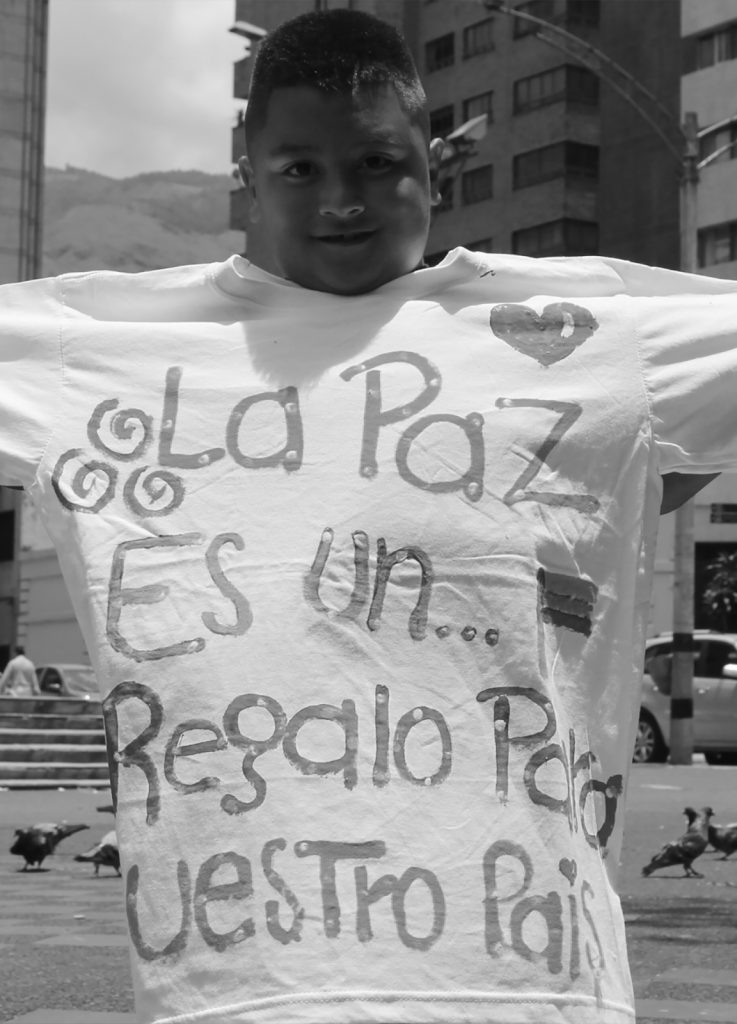

The “peace signing” in Montes de María carried a dual message: First, the action demonstrated that an organized, active citizenry had the power and ability to sign a commitment to build a lasting and stable peace in Colombia with or without an official, state-sanctioned process. By gathering in a public square, previously marked and symbolically represented as a place of war, the members of the Espacio Regional reclaimed their territory not as a place of violence, but one of peace. Second, the symbolic political action served as a reminder to the elite negotiators in Havana that grassroots peacebuilding efforts were central to the legitimacy and implementation of national accords. As they filed forward, one by one, to sign their names on the large banner hanging in the square, “We sign peace in Montes de María,” they claimed ownership over the peace accords, made their presence and work for peace visible in a context otherwise dominated by images of elite, negotiators seated around a table, and demanded active participation in the process.

A few months later, the FARC and the Colombian government signed the peace accords, marking a political end to over a half-century of war. Despite the “historic” achievement, however, Colombian citizens rejected the accords by a razor-thin margin through popular referendum on October 2. In the aftermath of the plebiscite, the Espacio Regional once again organized a mass-media campaign to circulate images of their March 15 peace signing. Despite political uncertainty, they reiterated, they remained committed to build peace “from and for the territory.” As mass mobilizations took place across Colombia, the images and statements from Montes de María circulated throughout the country, putting political pressure on the opposition to uphold the negotiated peace accords. One month later, a revised and final accord was signed and ratified by Congress.

The discourse of “postconflict” betrays both the ways in which peace is built in the midst of war as well as the workings of violence that extend into the aftermath of war

What factors and conditions enable peacebuilding coalitions, like the Espacio Regional, to cultivate the capacity to respond constructively with purposeful action in the face of setbacks, struggles, and unforeseen, life-threatening challenges? The answer to this question requires a much wider temporal horizon than one focused on the spectacular, single events of signed peace agreements. Indeed, the work of the Espacio Regional in Montes de María began long before declarations of a “new, postconflict” era. Members of the Espacio Regional had dedicated their lives to the daily labor of peacebuilding for the last several decades, working to create spaces of healing even in the midst of war. The discourse of “postconflict” betrays both the ways in which peace is built in the midst of war as well as the workings of violence that extend into the aftermath of war. Most alarmingly in Colombia, over 400 social leaders have been assassinated since the signing of the peace accords. The temporal and directional language of “postconflict” erroneously suggests that conflict operates within a linear framework and that reconciliation follows progressive, sequential stages once conflict is declared “over.”

The Espacio Regional, however, provides us with an alternative understanding of healing – not as a sequential line, but rather as a circle. Every month for the last several years members of the Espacio Regional have met together for an open dialogue. These sustained, monthly circle dialogues have worked to deepen and widen processes of relationship-building in a context of profound distrust wrought by a half-century of war. The Espacio Regional’s overarching mission is to foster dialogue with “unlikely actors across unequal differences” and “reunite equals across disagreements”.

Healing does not emerge from a one-time event, but through a dynamic, indeterminate, and continuous process of peacebuilding

The coalition works simultaneously to strengthen alliances and capacity for collective action within grassroots peace movements as well as rebuild trust across enmity lines. Members of the Espacio Regional advocate for change through direct and sustained engagement with “improbable” actors that have deep influence in the region, including the state, the private sector, multinational corporations, and (I)NGO – many of whom are responsible for the harm and violence suffered in the region. With a commitment to proximity and permanency, the Espacio Regional has created a space where unlikely actors come together to meet across difference. The monthly dialogues disrupt unequal power relations constructed through the false distinction between “experts” and “recipients,” through the construction of a collective agenda, built by consensus among grassroots movements. In doing so, the Espacio Regional has built a platform that is capable of creatively responding to rather than reacting against unexpected challenges – like faltering peace negotiations, the popular rejection of the peace accords, the staggering assassinations of social leaders in Colombia, and changing presidential administrations. Healing, here, does not emerge from a one-time event, but through a dynamic, indeterminate, and continuous process of peacebuilding.

The monthly dialogues allow the Espacio Regional to resist the “currents of the coyuntura” and remain steadfast in their commitment to building peace, responsive to the shared priorities of their communities. The dialogues provide an open space of trust where people can express their grievances and sense of deep loss while also imagine, name, and actively build hoped-for-futures. This multigenerational temporal horizon enables members of the Espacio Regional to simultaneously reach backwards and forwards, holding both memory and imagination together. Healing is aural rather than sequential.

We must find ways to recenter the lived experiences of local communities and work to build safe containers that can hold together a multiplicity of voices across difference

The metaphor of the Tibetan singing bowl captures the Espacio Regional’s process of social healing. Made up of a thin-walled brass container, the Tibetan singing bowl has a long history that traces back primarily to Buddhist meditation and healing practices. As the felt-tipped drumstick circles the rim of the bowl, the iterative movement produces vibrations. The bowl creates a container that holds these vibrations, allowing them to interact and generate frictions that eventually give rise to sound. For the vibrations to interact and give rise to sound, they must be held in close proximity. Sound emerges through multidirectional, circular, and iterative movement. Like the Tibetan singing bowl, the Espacio Regional engages in a permanent process of iterative, sustained, circle dialogues. The repetition of the monthly meetings is not directionless, but rather part of a purposeful, multidirectional process that deepens and widens the conditions necessary for change and healing. As distinct voices – lived experiences, grievances, concerns, proposals, and hopes – circle around and interact they also reverberate into a wider context, bridging the chasm between community-level processes and wider social change. Sound expands, moves out, touches, and surrounds the space within its reach. Sound does not emerge from a single vibration, but from multiple and diverse vibrations that interact, producing generative frictions. Importantly, sound cannot be sustained through a one-time event, but requires continuous attention and care. An aural understanding of healing as a multidirectional, permanent, indeterminate, and continuous process links individual healing to collective reconciliation. Social healing does not emerge from short-term, top-down, and bounded projects with end dates, but requires a commitment to permanent processes of relationship and trust-building that allow communities to be wakeful and responsive to violence found in daily life.

As peace scholars and practitioners, the pressing challenges facing our world demand that we decenter short-term and bounded approaches to peace that focus attention solely on spectacular, single events. Instead, we must find ways to recenter the lived experiences of local communities and work to build safe containers that can hold together a multiplicity of voices across difference. Social healing asks that we continuously nurture, care, and cultivate the ground that gives rise to daily practices of living that make resistance, resiliency and human flourishing simultaneously available rather than sequentially ordered.

Research for this essay was made possible through the generous support of Fulbright, USAID, the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, and the Kellogg Institute for International Studies. My current writing is supported through the 2018-2019 United States Institute of Peace Jennings Randolph Peace Scholars fellowship. As always, I am particularly grateful to my Colombian partners, including Sembrandopaz, the Espacio Regional de Construcción de Paz de Montes de María, the Proceso Pacífico de Reconciliación e Integración de la Alta Montaña and the Jóvenes Provocadores de Paz.

Photography : Campaign for the yes to peace in Colombia / Andrés Fernández Sáchez

© Generalitat de Catalunya