Since the election as president of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in July 2018 there have been countless debates and proposals about implementing transitional justice in Mexico. The initial announcements of pacification –talking about amnesties and truth commissions, and a social approach to the fight against crime that dealt with its socioeconomic causes instead of repressive strategies– generated confusion. They also even provoked hostility among some victims and participants in hastily organised forums. Civil society organisations with a long record of defending human rights and academic circles joined the debate, trying to formulate proposals. However, as became clear in the last months of 2018, this dialogue had very limited results given the lack of clarity of what had been announced by the then president-elect.

The imprecision of the announcements, the particular nature of the violence that affects Mexico, and a history of mistrust between the state and civil society have all made it difficult to define a coherent policy that responds to the need for security and justice. Part of this confusion has been created by the use of the concept of transitional justice, a notion that is open to different interpretations and can easily be manipulated.

Context and legacy of violence in Mexico

The degree and intensity of violence in Mexico exceeds anything one would expect in a society that supposedly is not involved in an internal armed conflict, has democratic institutions and has a long republican tradition. The causes of this violence vary in each region, but they originate from a combination of organised crime and the actions of state agents, whether at the municipal, state or federal level. The lines of separation between them are diffuse, since the networks of corruption of organised crime and state agents are obscure, given the lack of adequate judicial investigations. Indeed, the levels of impunity are putting into question the existence of the rule of law in many parts of the country, where public prosecutors and the police have very little credibility.

However, this situation is not entirely new. The figures for homicides and human trafficking have undoubtedly increased massively over the last ten years, but they were also high in the 1990s. To this one must add a history of state repression, massacres and enforced disappearances, such as the massacre of students in Tlatelolco in 1968, the so-called dirty war, and disappearances carried out in the 1970s. The clear up rates and application of justice in these cases have been practically zero, despite the creation in 2002 of a Special Prosecutor’s Office for Social and Political Movements of the Past.

A frequent complaint among victims and civil society focuses on the inability of prosecutors, at the state and federal levels, to investigate these crimes, which adds to their lack of autonomy. Some accuse these institutions of having cultures of indifference and neglect, particularly in relation to victims who are poor. The evidence of impunity seems to support these critical opinions. This is in contrast with the official legal guarantees, particularly with the framework of the Constitution, celebrated as one of the most advanced in its recognition of the rights of victims. The chasm between the declared norms and their effectiveness is disconcerting and seriously affects the credibility of the democratic system.

The pressure from victims’ movements and civil society for substantial changes in the face of the high rates of homicide, impunity and disappearances has led to several reforms

In recent years, different movements of victims and civil society have pushed for more substantial changes, first in response to the massive number of cases of kidnappings and extortion; then in reaction to the high rates of homicide and impunity and, later, to the large number of disappearances. These movements have given rise to several reforms, some of which actively involve civil society and victims’ organisations, such as the General Law of Victims; the General Law to Prevent, Investigate and Punish Torture; the General Law on the Enforced Disappearance of Persons; and the replacement of the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) by a General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic (FGR). These changes preceded President López’s campaign, and the norms and institutions created bring significant opportunities. However, the greatest opportunity lies in the accumulated experience of organisation, activism and ability to exert influence reflected in these reforms, and which will be necessary to continue moving forward.

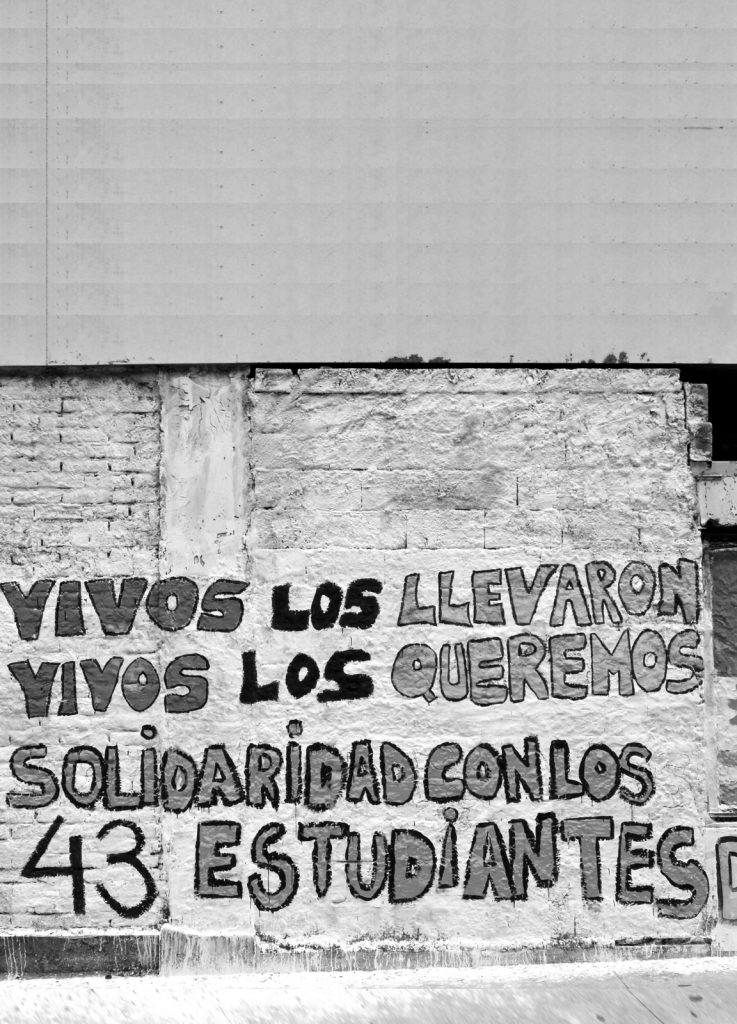

An iconic case that contributed to this process is the strong reaction generated by the forced disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa in 2014, followed by the massive clamour and international pressure in the face of the absence of effective investigations. However, the visibility of this case should not overshadow the broader process described above. The case has undoubtedly helped to give strength to a movement that demands truth and justice, but that “should cover the 40,000 disappeared, and not just the 43”, as different organisations demanded during the visit of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in April 2019.

The position of President López Obrador before this situation has been ambivalent. The campaign promise to return the soldiers to their barracks and to professionalise the police was abandoned days before assuming the presidency, in the light of the fragile security situation and the need to count on the support of the armed forces. The commitment gave rise to the creation of a National Guard: this was to be headed by a civilian, but a retired army general was put in charge.

Relevance of experiences of transitional justice in this context

Is transitional justice useful in this context? One of the first debates that arose within civil society concerned the definition of the transition: whether the election of a president who broke the two-party system of the PRI and the PAN could be described as such, or if we were talking about a continuation of the unfinished transition initiated by President Fox in 2000, after 71 years of domination by the PRI. To this confusion was added the use of language of reconciliation and amnesty that seemed to many victims a new name for the historic impunity. The use of references to Colombia, where the peace agreements contain amnesty provisions, significant reduction of sentences and alternative sanctions, was not justified in a situation where organised crime has no political motivation nor incentives for demobilising. For these reasons, it is highly advisable to avoid the language of transitional justice that generates such confusions. This does not preclude taking into account different experiences of transitional justice insofar as they offer useful lessons, particularly for their capacity to respond to massive or systemic crimes, in contexts of the fragility of institutions.

How can one respond to the need for justice in a context of massive violations, with insufficient or restricted power, limited capacity and resources, and institutions committed to impunity?

The first consideration is to remember that transitional justice is not a discipline in itself with a rigid framework, but rather emerges from very concrete experiences. First from fairly defined transitions between dictatorships and democracies in contexts such as Argentina, Chile, Eastern Europe and South Africa, and then in post-conflict situations, such as Guatemala, El Salvador, East Timor, Peru, Sierra Leone and Colombia1. These are diverse experiences, which respond to different contexts and conditions of power, resources, social organisation and institutional capacity2.

It is important to examine the first experiences, implemented before these notions had been transformed into dogma, because in those it is clear that what they were trying to do was not apply a “model”, but rather to resolve in some way the dilemmas between the demand for justice and the political and institutional capacity to achieve it. This requires us to pose questions like those formulated in these countries. How can one respond to the need for justice –understood in a broad sense, not limited to but including criminal justice– in a context of massive violations? How can one do that with insufficient or restricted power, limited capacity and resources, and institutions committed to impunity? The complementarity of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-repetition arises later. These points help us to examine different aspects, but they can not be considered a straitjacket, neither that it is imperative to implement these processes all at once. Precisely in these countries the successful experiences are those that take into account the balance between what is asked for and what can be guaranteed.

The contribution of transitional justice in Mexico should not necessarily be in identifying what the transition is, nor in defining the period that a truth commission should cover. Nor can it be based exclusively on the creation of institutions –this is a country with a history of large institutions, replicated in each state and with limited effectiveness– or in issuing new legal norms which are very exacting, but which have scarce application and have proven to offer limited accessibility to victims. Its contribution should start from asking what is the truth that Mexico needs to clarify and recognise. The country and its democratic institutions must ask themselves what are the lessons that must be drawn from so much violence and impunity. It is also necessary to define what form of justice can guarantee non-repetition and strengthen the rule of law, when existing institutions have systematically failed to offer justice. In matters of reparations, the authorities must ask themselves what are the consequences of the most serious violations committed and how to respond to them to ensure that all the victims of those violations have access to sufficient but feasible forms of reparation. Finally, the country and its authorities should not simply establish new institutions or approve new laws, but answer the question about what mechanisms should be established to ensure that these levels of violence and complicity do not continue. These questions must be formulated while recognising the history of the persistence of violence and impunity, limited resources, and the other priorities of the country, which include overcoming poverty and widespread marginality. The contribution of experiences of transitional justice should not be to replicate the institutions that these experiences have created in other contexts, but to formulate these questions with a sufficient dose of realism.

Strategies to carry the process forwards

The need to be realistic doesn’t mean not being ambitious. It means taking advantage of the opportunities and prioritising those that can lead to steps forward in the short term. These steps forward can help win support and create confidence both among victims and among the general population in the possibility of gradually demolishing the structures of impunity, but without pretending that this can be done at a stroke. It is crucial to examine the opportunities and see which of them can open up new possibilities. Some have already been identified by civil society organisations, and these can undoubtedly be key partners for the Government, to the extent that both parties are willing to listen to each other and collaborate.

One of the opportunities is the political support that exists for the search of missing persons, strengthened following the visit of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The National Search Commission now has leadership, political support and resources on a scale that it never had before, and is backed up by a strongly organised community of victims. The task is enormous and immensely complicated. However, the possibilities exist of offering some concrete results in certain less complex identification processes, while at the same time initiating a broader plan of identifications. These particular results and the existence of a plan could increase the pressure to do justice in these cases. The determination of patterns of disappearances, making it possible to identify the institutions, criminal organisations and authorities that may be involved, could help to generate the level of indignation and even public anger that societies need in order to advance towards more profound changes, particularly in matters of justice.

A second opportunity is the widespread disappointment with the Executive Committee for the Attention of Victims (CEAV) and the discredit of a reparations policy designed without a clear awareness of its limitations in capacity and resources. Paradoxically, this situation could serve to explore a different reparations system, restricted to the most serious violations and without distinction of state or federal jurisdiction or geographical location, but without affecting the acquired rights or expectations of reparation created by the General Law of Victims. This would imply the creation of a parallel program, implemented through a separate team within CEAV, that would record, in a simplified form and for the sole purpose of this new program, the direct victims and their closest relatives in cases of grave violations, such as death, disappearance, serious sexual violence, torture, trafficking of persons and serious incapacitating injuries. This program could consist in a series of standardised measures common to each category, as has been proposed by the coalition of civil society organisations working on this issue. This would allow a significant group of victims to begin receiving concrete forms of reparation within two years, while at the same time restoring the prestige of CEAV and of the state.

In Mexico, the challenge is in how mechanisms against impunity can generate a transition. Advances should focus on obtaining results that respond to the rights and demands of the victims, on strengthening the capacity to respond of the State and civil society, and on generating greater backing from the population

Other opportunities require further exploration, such as the formation of a team to analyse the archives of the Centre for Investigation and National Security (CISEN) as a source of information for the search process, judicial investigations and a gradual process of clarification of patterns of violations and of the truth. At some point, the vetting process for National Guard personnel could be subjected to revision, so that complaints about the possible participation in human rights violations or abuses of power by candidates would put into question their suitability. In this, the files of the National Human Rights Commission and the information in the hands of civil society organisations could be useful. The standards for this would not need to be the same as for criminal investigations, since the only consequence would be the exclusion from forming part of that body. Finally, the transformation of the PGR into the FGR could be an opportunity to establish a team specialised in methods of investigation by patterns, focusing not on clearing up countless individual crimes but rather on identifying criminal networks and large scale criminal plans. That could make it possible to identify those responsible within the illicit networks, including the direct leaders but also the financial and political operators that form part of them. The dismantling of some of these networks could give confidence to the population and give lessons that would improve the capacity to investigate and to make the best use of investigative resources. Such investigations could make victims feel that the response to their rights is not limited to the search for their relatives or to modest reparations, but also effective justice, and that the dismantling of such organisations will diminish the possibilities of such violations continuing.

These possible strategies could lead to excessive expectations. It should be noted that things will not be easy. One of the lessons of the processes of transitional justice is the tendency of systems of impunity just to adapt themselves, to resist changes and to stall. Perhaps the conditions do not exist to do everything that needs to be done, so a start must be made with policies that not only generate tangible progress, but also produce results that permit advances in new processes of truth, justice and reparations. In a case such as Mexico, in which there is no transition, the challenge is how the mechanisms against impunity can generate, precisely, a transition. The steps forward should aim at obtaining results that respond to the rights and demands of a significant number of victims; also at strengthening the capacity to respond of the state and civil society, and in generating greater support from the population. That requires, on the side of state institutions, not only efficiency, but also maintaining a frank and constant dialogue with the various victims’ organisations and keeping the doors open to suggestions and to monitoring by a civil society. Conversely, human rights and victim organizations should take the risk of becoming involved in solutions that are perhaps less than perfect, but are feasible and may be able to generate the conditions for future advances. It requires, however, the greatest responsibility from the government, which, in turn, must take the initiative and lead a process based on consultation, listening to victims and civil society, and taking their rights seriously.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cristián Correa is a lawyer with experience in the definition and implementation of transitional justice and on reparation policies for massive violations of human rights at the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), where he is a senior associate. From the ICTJ he has offered advice in different countries, such as Peru, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Colombia, Nepal and East Timor. Previously he was the legal secretary of Chile’s National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture, and worked in the Ministry of the Interior and in the Presidency of the Republic, coordinating the implementation of reparation policies and providing advice on human rights policies.

1. Other post-dictatorship experiences refer to Morocco, Brazil and Tunisia, while Kenya is a particular case that combines authoritarianism with political violence.

2. See Roger Duthie and Paul Seils (eds.), Justice Mosaics: How Context Shapes Transitional Justice in Fractured Societies (International Center for Transitional Justice, New York, 2017), and particularly Roger Duthie, Introduction, 8-39.

This is a translated version of the article originally published in Spanish.

Fotografia Manifest for the disappearance of 43 students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Normal School in Ayotzinapa (Mexico)

© Generalitat de Catalunya