Editorial

From the war on terror to the uprisings in the Arab world, an accelerated decade

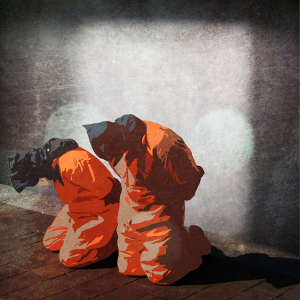

Image: Troy Page / t r u t h o u t

The optimism of the post-Cold War period, which began with the hope that some of the swords could be turned into ploughs as a result of the "peace dividend" (the allocation of part of international military expenditure justified by decades of East-West confrontation), ended abruptly a decade ago, with the attacks of 11 September 2001 in New York and Washington.

As shown by the articles and the interview in this monograph issue, the attacks started an accelerated decade, which was full of changes in both the domestic, foreign and security policies of the United States, as well as indirectly in international geopolitics. The impact of some of those changes is still being felt today.

Although things have gradually changed, particularly since President Obama took office, there is still a great deal of work to be done. There are two key factors in any overview of the decade. First, the overall situation in the fight against terror, highlighted by the instability of the Arc of Crisis (Iraq, AfPak, Iran, the Middle East) is structural and will not necessarily improve with the departure of US and NATO troops scheduled for 2014. Among other factors, this is due to the revival and capacity for action of the Al-Qaeda franchises with more local roots that are more distantly related to the central "brand." Second, and more positively, the Arab uprisings that began in Tunisia have shown that people, despite decades of dictatorship and repression, can mobilise to meet basic needs as important as survival, dignity and freedom, regardless of their physical security, and confront the police and military. The Arab world has risen up for the first time in two centuries, and its people have made their demands against their own regimes and governments rather than against the neo-colonial and colonial powers, rendering worthless the thousands of documents suggesting that freedom is a value that is not understood by the Arabs.

These two factors allow us to draw a final conclusion: there are no shortcuts to solving complex problems, such as the political violence and terrorism (an extreme form of political violence) that are so prevalent in the twenty-first century, and which are far from being specific features of Islam or the Middle East (as the recent events in Norway and extreme right terrorism keep reminding us).

For this reason, it is necessary to emphasise the analysis and proposal made by Fred Halliday in 2004 regarding the fight against terror:

The central challenge facing the world in the face of 9/11 and all the other terrorist acts preceding and following it, is to create a global order that defends security while also making real the aspirations to equality and mutual respect that modernity itself has aroused and proclaimed but has spectacularly failed so far to fulfil. Terrorism, then, is a world problem in cause and in impact. It should be addressed in a global, cosmopolitan, context.

(The conflict will endure for decades and the outcome of which is not certain, but it must be fought)

In engaging with it, citizens need five things: a clear sense of history; recognition of the reality of the danger; steady, intelligent, political leadership; the building of mass support within European and global society for resistance to this new and major threat; and above all, our best defense, a commitment to liberal and democratic values.1

1. Fred Halliday, "Violence and Politics", in Political Journeys. The Open Democracy Essays, Londres, Saqui Books, 2011, p. 180. (Back)