EDITORIAL

To build peace we need ideas and values, but also instruments

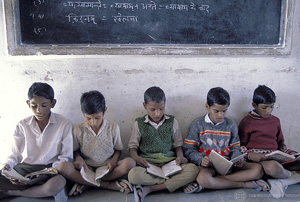

Photo: World Bank Photo Collection

The theme of this issue of Por la Paz/Peace in Progress is the single subject of the role of supervisory committees and the analysis of textbooks in the creation of a culture of peace and in education for peace.

As I provocatively said a few years ago, educating for peace, human rights and solidarity in the academic and social field calls for radical prudence: prudence, because it is necessary to progressively set reasonable objectives in order to achieve changes, and radical, meaning going to the roots and starting from the roots, because we have to consider the final objectives from the very beginning, both in analysis (what is criticised and what needs to be changed) and in expected results (what is expected in order to build). Radical prudence against tactical impatience.

I will begin by putting the importance of the analysis of textbooks and school handbooks into context:

First, having tools to judge the quality of textbooks is normal and especially important in southern European countries, where often not only compliance with curriculum guidelines, but also the choice of textbooks is a decision taken by the educational authorities. There are many approaches that make it possible to analyse the contents, activities, methodologies and even formal aspects (from the legibility of the type to the kind of language used).

Secondly, given the importance of textbooks in the educational context of southern European countries, since its foundation in 1946 UNESCO has included the preparation of textbooks as part of its educational strategy, based from the very beginning on the principle of human rights, promoting the creation of textbooks and regularly offering workshops that integrate several analytical tools, such as guidelines for supervisory committees. Other international bodies have also prepared guidelines and recommendations in this regard[1], and there are even currently some very ambitious (and controversial) initiatives underway, such as the preparation of a handbook containing shared narratives about the conflict in the Balkans. All of the above means that we can say that UNESCO, as can be seen on its website, considers that handbooks and educational materials "when well conceived, transmit concepts and competences that promote peace, human rights and sustainable development", especially within the field of education for peace and work for international understanding.

Thirdly, since the 1970s the review of textbooks, especially after a preliminary report, has been focused on constructive and positive analysis aimed at improving the products, with very simple reading guidelines.

The instrument that is analysed in this issue is the role of the critical, constructive analysis of handbooks and textbooks as an objective part of education for peace. This is a tool that, by demanding that we work with the authors of handbooks and with publishers, provides opportunities for joint work and a fabric of mutual understanding between peace and development specialists, teachers, authors, publishers, educational authorities, parents and the educational community in general (including students) in attempting to improve competences[2].

A task that is undoubtedly modest, some will think. However, certainly very effective, because as Isaiah Berlin noted, "we can only do what we can: but that we must do, against difficulties".

[1] See, for example: Council for Cultural Co-operation (1995), Against Bias and Prejudice: The Council of Europe's Work on History Teaching and History Textbooks, Council of Europe, Strasbourg; Stobart, M. (1989) Fifty Years of European Co-operation on History Textbooks: The Role and Contribution of the Council of Europe. Internationale Schulbuchforschung 21, 147-161.